Think of a time that you experienced conflict when working in a team (e.g., Work team, your student organisations, sports team, class teams, etc.) and describe the life of that conflict—what was the conflict about? How did it start, evolve, and finish? How many team members were involved when the conflict started and when it ended?

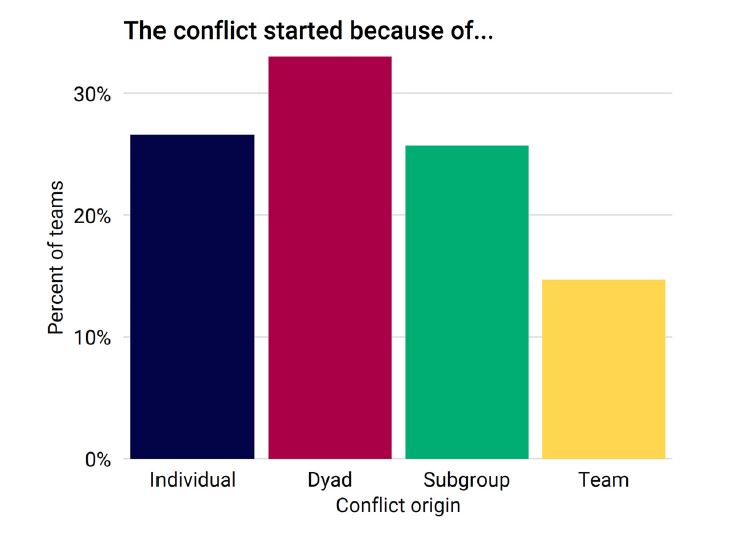

The conflict started because . . .

(1) of the actions of one person,

(2) there was a conflict between two people,

(3) there were coalitions (e.g.,subgroups) within the team, or

(4) there was a conflict that involved everyone.

Watch 4 minutes from the film Succession to observe how a vote of no confidence in the Chairman accelerates from a conflict via an individual to conflict within sub groups, to conflict within the entire team.

As Phaedrus cautioned in the Plato dialogues (circa 370 BC), ‘‘Things are not always what they seem; the first appearance deceives many.’’

Is intragroup conflict a team level state of discord? Is intragroup conflict truly uniform? Is it something static that can be measured at a single point in time? What does conflict really look like in teams and how does it ultimately influence team performance? Does it matter where team conflict originates and how it evolves?

Let’s dig deeper by asking questions:

Where does conflict within teams originate?

Does team conflict occur most often because two team members hotly disagree, while their teammates either steer clear or take sides? Or, does a single argumentative member cause conflict?

Current research via Johnson Cornell College of Business identifies four potential origins of team conflict:

- Individuals

- Dyads

- Subgroups

- Whole team.

Let’s start at number 1; Individuals;

1. Individuals

‘‘Many of the conflicts surrounded one girl on the committee that opposed every suggestion the committee or I made.’’

‘‘One of the players on our team didn’t get along with anyone else . . . he always wanted to stand out and make himself look better than everyone else. . . Other players on the team began to get annoyed with [this team member] only thinking about himself and not caring about the success of the team.’’

‘‘I was once involved in a conflict that arised [sic] with a new person, a medical director, joining the company. Rather than experiencing our culture or ways of working, the person immediately formed a silo with his medical team, shutting down information flows to the commercial part of the company.’’

The above are real-world narratives arising from an Individual Origin Conflict frame.

The behaviour and actions of a single individual can easily cause team conflict. ‘‘Bad apples’’ (Shah et al.) are toxic individuals who chronically display behaviours that asymmetrically impair group functioning’’

Their low level of agreeableness causes them to disregard interpersonal relationships; their lack of conscientiousness causes them to show minimal concern about contributing to team tasks; and their emotional instability restricts their ability to manage external stressors—all of which create turmoil that potentially spreads through the team.

Be mindful – Bad apples are distinct from ‘‘principled dissenters’’ who push teams to think critically, explore options, or evaluate different perspectives. Embracing dissent is sufficiently critical for team success that some scholars suggest manufacturing disagreement in the form of ‘‘devil’s advocate’’. Creating cultures and climates of Psychological Safety, to support principled dissent, has become salient and relevant in today’s knowledge economy.

Bad apples create relationship conflict, devil’s advocates create task conflict, and both can be individual instigators of intragroup conflict.

2. Dyads

‘‘At first these two debated about differing ideas on what the venue and theme should be. As time went on and neither gave way on their idea it became more about winning to them than about finding a good working solution.’’

‘‘In essence, [team member] and I just did not like each other. . . . Because [team member] and I were so focused on our own position and our own goals during the conflict, our conflict became both personal and extremely competitive. We were both driven to do whatever it took to beat the other person, not just in races, but in workouts and team popularity as well.’’

‘‘I had two members in my working-team . . . [who] did not like each other too much. When one was arguing in one direction, the other one made a strange face, making clear that he/she was thinking this is nonsense. It wasn’t a constructive way of working with each other, showing off too much of the emotions behind it.’’

Do you recognise any of the dyad narratives above, the most salient context in which team conflict is expressed and experienced?

Without being behaviourally involved, two teammates can be in conflict with each other but not with other members.

Two members may experience relationship conflict as they clash due to incompatible priorities or differences in values or world views. This signals a requirement for training to navigate communications across diverse team members.

Alternatively, two members may experience task conflict as they have different ideas for approaching team tasks because of diverse backgrounds, training, experience, or expertise. I’ve written about this before in my blog How conflict in a team can interrupt honest and open reporting cultures.

Dyadic conflict can result from perceptual differences leading to distrust, miscommunications leading to misunderstandings and insults, poor interactions and power struggles, incongruent goals or competing interests in negotiations or differences in power and status.

3. Subgroups: Warring factions

‘‘For our team the conflict focused on what each of us believed the vision of the company should be and the approach that we should take. Three groups of people formed during this conflict. One group believed that we should focus on creating an ecommerce business plan focusing on selling men’s fashion. The second group believed that we should focus on creating a plan for a slow-fast food chain that resembles Chipotle Mexican Grill, and the third group believed that we should focus our efforts on creating the next big social media platform that connects people through the use of music.’’

‘‘He and a few others wanted to make this pamphlet so we could hand it out at any community events we were participating in and while we were door knocking for our candidates. . . . Both [team member] and [team member], the higher up officials, completely disagreed with the idea of the pamphlet. They thought it would separate us from the other Senate Districts, which is something that they don’t want to see happen.’’

‘‘The first sign of conflict came when the three people assigned to research kept putting off their research. The rest of the group was unable to start their work because the research they were supposed to be doing was imperative for us to complete our work. . . . Although there were a couple of us who were still working hard at getting the project done, the majority of the team had already checked out. The division between the slackers and workers grew.’’

We saw an example of Subgroup conflict in video I shared at the beginning of my blog.

The fault lines are team member diversity, power, and politics in mixed-motive teams. Studies of team member composition and diversity show that different characteristics or interests among subgroups frequently produce conflict. In large teams, some members may not be part of any subgroup but may simply observe the conflict that exists between subgroups around them.

Subgroup conflict may also depend on whether the teammates have aligned interests. Conflicting coalitions are likely to form when team members face social dilemmas—when collective and individual interests are misaligned.

The heightened salience of social categories can interfere with communication and information sharing, causing task and relationship conflict across subgroups.

4. The whole team: All-encompassing conflict

‘‘When we had our first meeting after the challenge was announced, everybody came up with their own idea on how we could build our robot. . . . Every member thought their idea was the best and wanted to use their own.’’

‘‘Last year I took part in a task force that aimed to implement a new Time & Attendance software solution for all the Business Units of the Organization I am working for. The task force was made up of 5 professionals: one project manager and one representative from each BU. We started sharing our local T&A practices and the requirements that we thought should be fulfilled by the new application. The conflict arose when all the BU representatives realized that they had different needs as far as rules and new procedure details. None of us initially wanted to grant room for changes to minimize the impact on the as-is local administration practices.’’

‘‘The conflict I specifically remember was when our team was losing to a lower-ranked team than us and we knew we should be beating them. . . . Members of my team, including myself, started to point fingers at one another rather than collaborating to build team morale. . . . As members started to call names and scream and shout at one another in the locker room after the first period, we began to lose sight of our task.’’

Whole team conflict as a point of origin is a pattern in which most team members are in direct conflict with each other. While observers may exist, the majority of team members are behaviourally involved in conflict, but team members may have varying involvement in the conflict.

Thankfully, conflict with a whole-team origin was found to be the lowest frequency of conflict.

Considerations

Train for Courageous Conversations – whether a Growth-shop for Speaking -Listening Up, to strike the right tone for Feedback or to navigate constructively for Diversity, Belonging and Contribution.

Alternatively Team Coaching, to help teams create better solutions through integrating divergent perspectives and sparking new ideas. By recognising and better investigating how members within the same team may come to view the same conflict in different manners, leaders may be able to better understand the nuances and dynamics of intragroup conflicts and leverage for the best outcome.

Maintain a constant flow of communication between the C-suite and employees, so that organisational purpose and decisions at the top are translated throughout all levels of a company. A good corporate culture also encourages employee autonomy so they have the freedom and trust from management to make a decision about a problem in real time.

Learn how to create Teaming Routines: Lead with humility, to manage work across geographic distance, or with varying disciplinary expertise, or involving complicated hierarchies of power.

Learn how to craft and support psychological safety in your teams where employees believe that candour is expected and welcome and that team members are upskilled in the tools to engage in Courageous Conversations. Encouragement is not enough – Explore Courageous Conversations Growth-shops.

It isn’t enough to say you’ll be transparent and open and use conflict constructively. Without an approach determined in advance, less assertive voices won’t be heard when there is a disagreement, and a blanket commitment to debate ideas has the potential to be interpreted as a license to aggressively advocate for one’s position (rather than consent to engage in an open-minded, collaborative discussion).

Please get in touch, I’d love to be of support.

Leave A Comment