Watch this short video as an example of how Conversational Goals can go awry.

Recently a relative initiated a conversation with me that at first felt like a very personal attack on my character. I felt defensive, upset and angry but thankfully I was able to recognise this as an opportunity to follow my own advocacy and framework for Courageous Conversations.

Despite my emotions, (and there were many!) I was able to identify what was important to me in the conversation and to get into the conversational lane that could serve us both.

Much of what was being launched at me was factually incorrect and as much as I wanted to correct my relative with counter facts and ‘be right’, I saw my goal as focussing on preserving our relationship.

Two hours later we were both exhausted and alive to pursuing different and multiple goals simultaneously. Like all Courageous Conversations we both wanted to make progress on issues that mattered and preserve and strengthen our relationship.

What does conversational success look like?

The meaning of success in conversation depends on people’s goals.

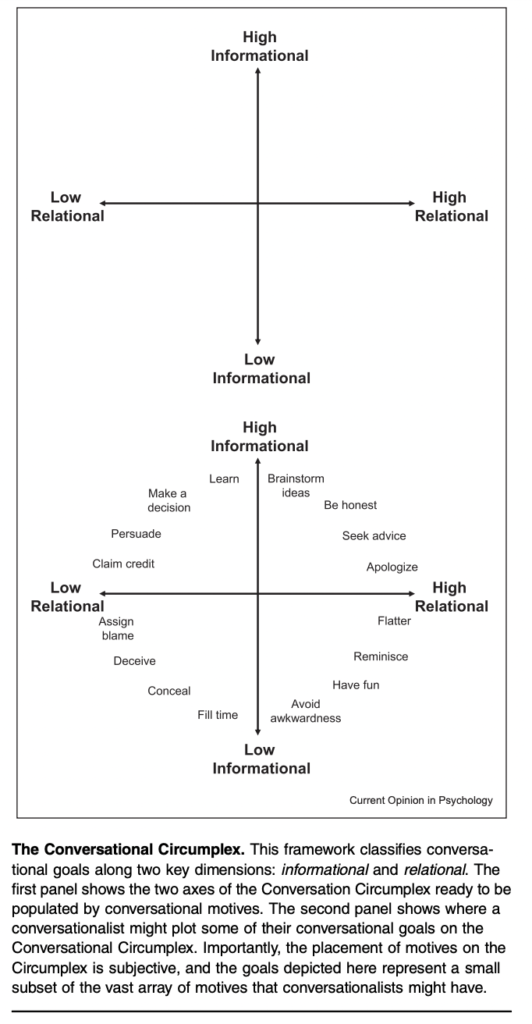

Let’s have a look at the Conversational Circumplex model that supports the training for Courageous Conversations.

The Conversational Circumplex is used to classify conversational motives along two key dimensions:

1) informational: the extent to which a speaker’s motive focuses on giving and/or receiving accurate information; and

2) relational: the extent to which a speaker’s motive focuses on building the relationship.

People communicate constantly, and nearly every human activity involves a conversation. Conversation is a rich environment filled with verbal, nonverbal, and prosodic cues, and within every conversation, individuals pursue at least one goal, but often more than one.

Psychologists have demonstrated that human behaviour is often subject to a vast array of competing and complex goals. Researchers Michael Yeomans, Maurice Schweitzer and Alison Brooks assert that this is particularly true of conversational behaviour. That is, people pursue a broad set of goals in conversation beyond seeking to understand each other. In our conversations we aim to agree and disagree, to help others and hurt them, to fall in love and break up, to make decisions and avoid making them, to disclose and conceal information, to flatter and denigrate, to incite conflict and avoid it, and we do this on motives that vary idiosyncratically across people, relationships, contexts, and time.

I use the Conversational Circumplex model to underscore the multiplicity of conversational goals that people hold, and highlight the potential for individuals to have conflicting conversational goals that make successful conversation a difficult challenge.

This model helps to classify the many goals people pursue in conversation and how they can successfully and unsuccessfully understand and advance their goals within their conversations.

Returning to my conversation with my relative, I was keen to ensure accurate information and my immediate motive was to navigate through goals that would be characterised by high informational content. I chose verbal behaviours such as asking questions, providing ‘proof’, defending decisions and inviting brainstorming ideas. However and in contrast, my relatives’ goals were characterised by low informational intent which did not focus on the accurate exchange of information. Instead, my relative sought to fill time, avoid vulnerability, and conceal and discount information. Their verbal behaviours were characterised by dodging questions, joking, staying quiet, or lying.

Was I willing to trade off the health of my relationship for correct information? I wanted to preserve and strengthen my relationship and also wanted to make progress on the issues being shared and that mattered. I wanted both. But I felt stuck, feeling like I could only do one or the other or neither.

I chose to change my mental model, the way I saw the nature of our conversation. The shift was going from a one-dimensional view of the world to at least a two dimensional view.

A conversationalist with goals characterised by high relational intent seeks to build their relationship. These goals include objectives such as building trust, finding shared understanding and learning about each other. To advance goals with high relational intent, individuals may choose verbal behaviours such as apologising, making concessions, revealing a weakness or vulnerability, admitting mistakes, or flattering their partner. In contrast, goals with low relational intent seek to advance a ones’ own interests without regard for the relationship. For example, individuals seeking to advance goals with low relational intent may choose verbal behaviours such as claiming credit, assigning blame, withholding laughter, lying for their own benefit, or telling non-affiliative jokes for their own amusement.

As we navigate our social lives, we’re likely to pursue goals across all four goal quadrants: {high/low informational and high/low relational}. Each of the four quadrants includes appropriate goals for specific situations, but individuals who seek to simultaneously pursue motives in different quadrants on the circumplex will need to prioritise, reconcile, and manage the sequencing and transitions of their verbal, nonverbal, and prosodic micro-decisions within and across conversations.

Decades of research investigating individual judgment and decision-making reveal that people routinely err when forming judgments, preferences, and beliefs.

The Conversational Circumplex highlights how difficult each of these tasks can be, by illustrating the wide range of possible goals each person can have. As we strive to navigate conversations and advance our goals, we are almost certain to fall short. This is where upskilling in Courageous Conversation training, either via one to one online or group coaching, can support you

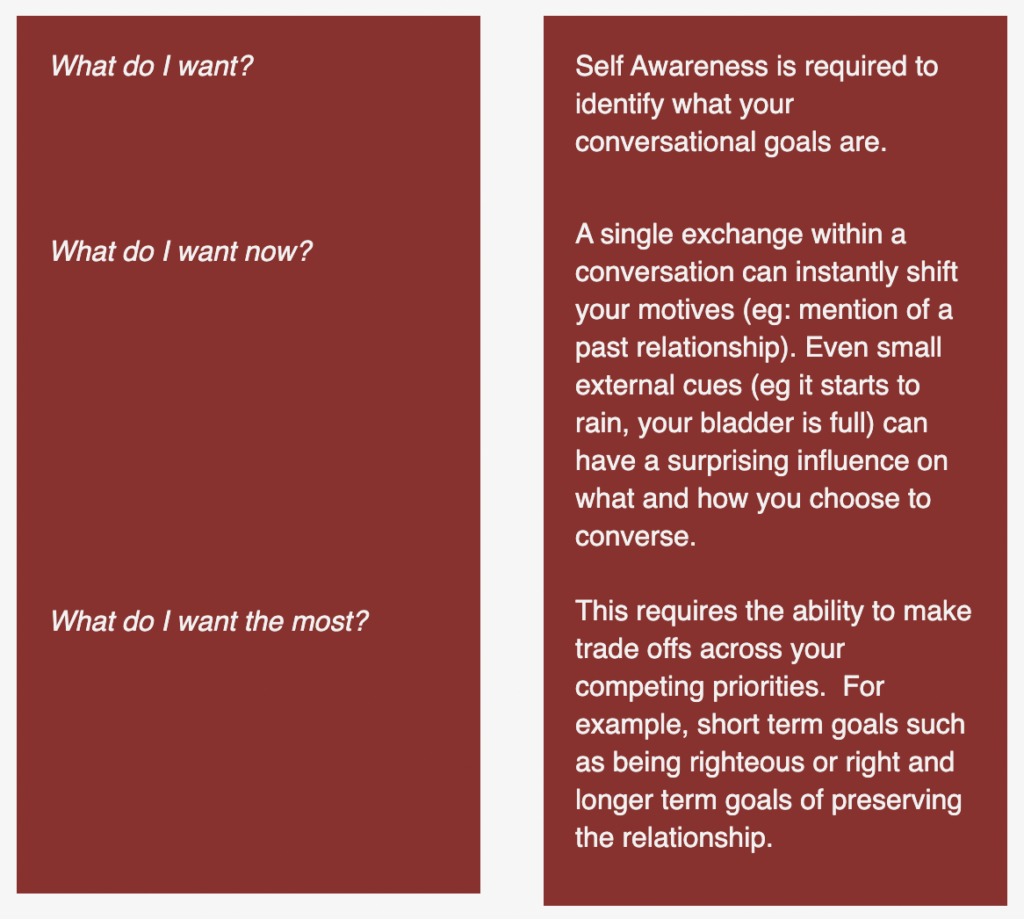

How to Identify your Conversational Motives

This is where Courageous Conversation training helps people to think concretely about what their goals are, whether they have too many, or too few, and how they might experience their goals as conflicted, or not. Even 30 seconds of forethought can help conversationalists to follow through on their intentions during the conversations.

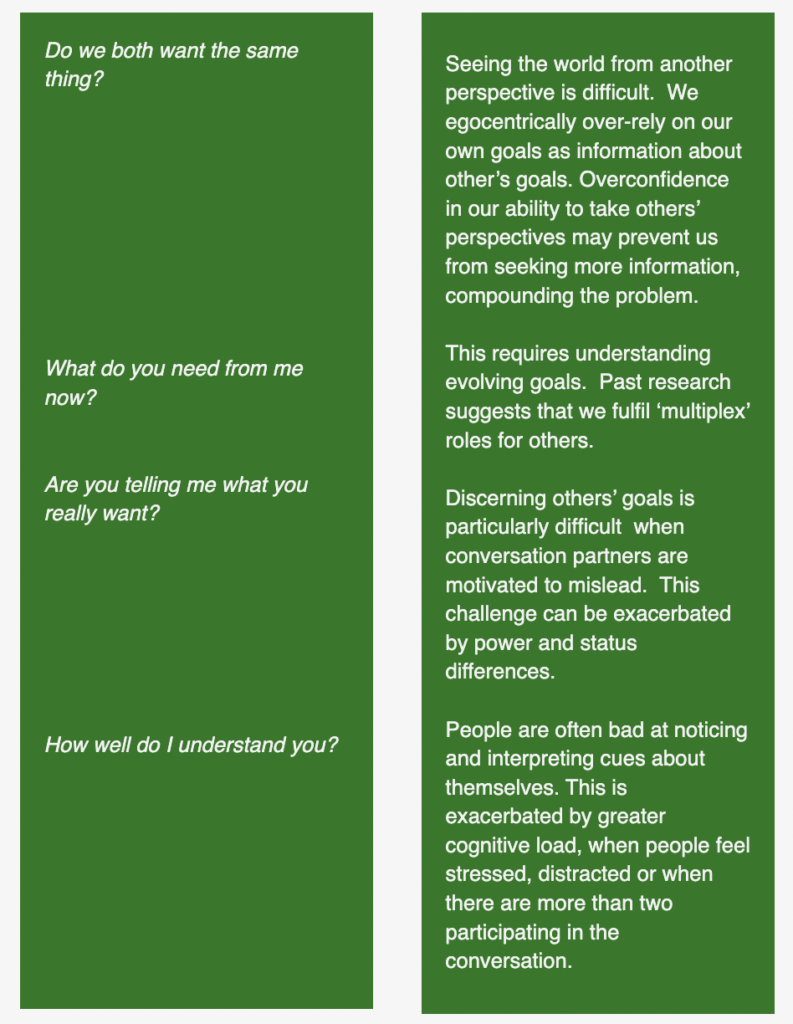

How to Discern your Conversational Partners’ motives

Translating Motives into Behaviour

Knowing is not enough when it comes to communication. We need to translate our motives into actions that actually advance our conversational goals. That’s because the cognitive complexity and time pressure of conversations may cause us to make poor choices in the moment.

Importantly, many behaviours may be surrounded by intra-psychic and interpersonal goal conflict. For example, imagine an individual who wants to voice a dissenting viewpoint but doesn’t want to seem grumpy or contrarian (intrapersonal goal conflict), and, at the same time, their conversational partner doesn’t want to be contradicted (interpersonal goal conflict). The decision to voice his or her dissenting viewpoint (or not) is fraught and the definition of ‘success’ or ‘failure’ will be highly context dependent.

By improving both our passive perception of others’ conversational behaviour and the active elicitation of information (e.g. via question-asking and reciprocal disclosure) we can improve our ability to recognise others’ goals and make conversational choices that advance both of our underlying interests.

If you enjoy my research and this blog I’d welcome you sharing with your network, friends and families!

If I can help you give me a shout-out to wendy@speakout-speakup.org