I’m placing this four- minute video right at the top of my blog as I want it to invoke your thoughts and feelings about how you hold yourself responsible for the words you use. As you’ll see, ‘rapping on bullshit’ is dishonest and inauthentic, fueling team conflict which can spill outside meetings into the corridors.

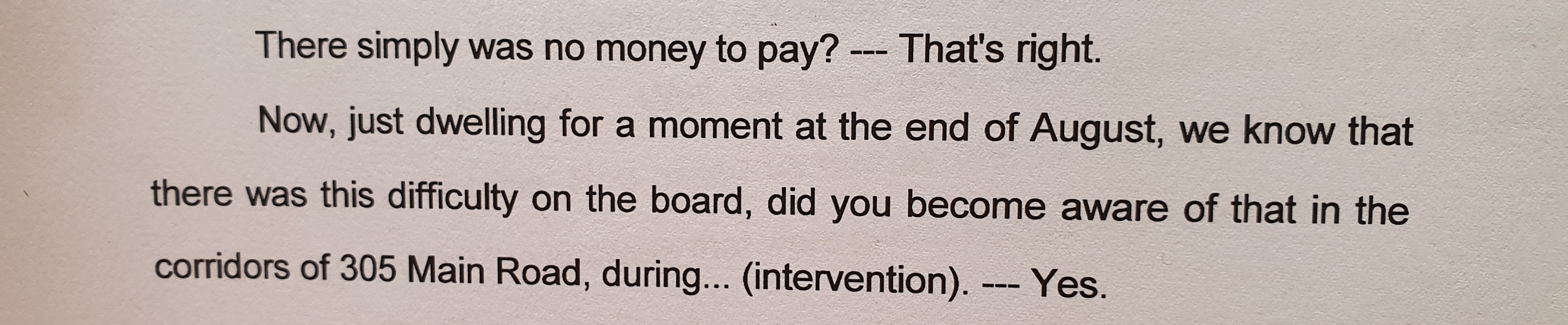

| One of the many problems at LeisureNet Ltd, the organisation I blew the whistle on, was that there was strategic attention deficit disorder that stemmed from the Board warring with itself. My executive team and I would spend months trying to nail down a new market and financial strategy. Meanwhile different directors were pushing in different directions, rendering each of us, as leaders, incapable of giving consistent direction to our teams. This wreaked havoc in the trenches. We felt that if the directors couldn’t get their act together on exactly where the organisation should be heading it was impossible for us to maintain a strong sense of purpose. One of my team called out their ambivalence with regard to these conflicts – “Why should I care? I know the priority du jour is going to change and what’s really expected of me is to make my boss look like he knows what he’s doing. Its not like we’re all in this together.” It was due to these unresolved disagreements and conflict that we were forced to take cues from the mutterings in the corridor, as revealed by this snippet from my trial testimony in the Cape High Court, with the judge asking me about ‘difficulties on the board’. |

More recently we’ve seen the exposure of Boeings’ internal emails and messages which highlight how their employees were raising concerns for its 737 MAX aircraft; amongst themselves, with no escalation. The result? The reactive grounding of the 737 MAX only after the two crashes which killed 346 people.

“The toxic tone of some of the emails suggests that there are numerous problems at Boeing,” said MIT Sloan senior lecturer Neal Hartman. “Of greatest concern is the fear that employees were either uncomfortable or not empowered — or both — to take their concerns to appropriate levels in the company.”

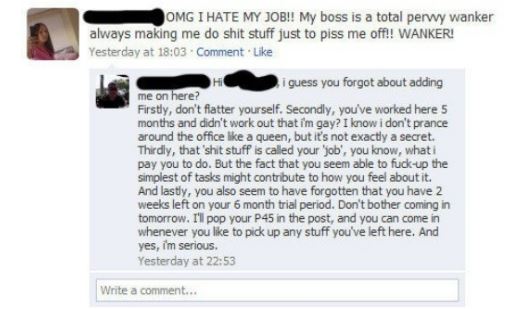

In this blog I want to focus on why, individually and in our teams, we struggle to effectively engage in disagreements, real debate that is robust so that teams can achieve their purposes. How do we avoid conflict spilling out and becoming a “corridor conversation’, or worse, a ‘social media soliloquy’?

The modern workplace is awash in meetings, many of which are terrible. As a result, people mostly hate going to meetings. The problem is this: The whole point of meetings is to have discussions that you can’t have any other way. And yet most meetings are devoid of real debate. When teams have productive disagreements during meetings, team members debate the issues, consider alternatives, challenge one another, listen to minority views, and scrutinise assumptions. However, many people shy away from such conflict, conflating disagreement and debate with personal attacks. In reality, managed friction produces the best decisions. UC Berkeley Professor Morten T Hanson found that the best performers are really good at generating rigorous discussions in team meetings compared to performers who are average or poor.

What are the signs that a disagreement has the potential to become a negative force in a team?

The first is the clear observation of emotions escalating, where disagreement becomes personal which in turn distracts from the task at hand. The second is when team members begin fighting about things that they don’t care about and aren’t that important, for example, the times to meet, the venue to meet at. These innocuous indicators signal that a team is in trouble and that there are bigger issues such as status concerns, respect and leadership issues.

Disagreements translate into conflict when one team member is listening to a group discussion and thinks ‘I really don’t agree with what’s been said here and I need to say something’ and speaks up about their disagreement. Team members are then given the opportunity to discuss and agree or disagree. Generally, one person will offer feedback on the points raised, such as “you think we should take strategy X. I think we should go for strategy Y’ and it’s at this point that there is a conflict between two people in the team. Others in the team can at this point choose to engage or not.

Conflicts at this stage are the most positive as the two team members are authentically engaging in different points of interest and information on an area that needs to be reconciled. However, as the conflict grows members of the group begin to make choices about not joining the disagreement due to the questions being thought about or they may begin to feel emotional as people start raising their voices in anger or frustration. They may join in for political alignment, to support their boss or another team member. This is the second phase of conflict, where sub groups start to form. The conflict escalates and intensifies and is more likely to become personal and destructive than the conflict with the two people who had different information. Members of the team who perhaps didn’t want to get involved get sucked in as well leading to a team brawl.

Some types of disagreements are worse than others. There are three types of conflict that can occur in teams and are likely to hurt team performance:

Task conflicts are the most productive in teams.

Task conflicts entail disagreements among group members about the content and outcomes of the task being performed. Task-related conflicts may facilitate innovativeness and better group decision making because they prevent premature consensus and stimulate more critical thinking, as long as team members can speak up and there is psychological safety.

The potential negative effects of task conflict on outcomes such as satisfaction, can be explained by self-verification theory (Swann et al., 2004), which suggests that team members become dissatisfied when they interpret challenges of their viewpoints by other group members as a negative assessment of their own abilities and competencies. These conflicts are a distraction and require resources that cannot be directly invested into task performance. A hijacked task conflict increases cognitive load, it also interferes with effective cognitive processes and may result in narrow, black and-white thinking, thereby obstructing group outcomes such as group effectiveness, creativity, and decision making.

Process conflicts are the most negative conflicts to occur in teams because they represent underlying, unresolved conflicts within the team eg: if you are unhappy about your status in the team but are unwilling or unable to speak up, you choose to create a conflict about roles and responsibilities. Process conflicts are disagreements among group members about the logistics of task accomplishment, the day to day work in teams: what time are we going to meet, who’s going to do what, where are we going to meet, what responsibilities each team member should have.

The negative effects of process conflict on group outcomes are thought to occur because the issues at the heart of process conflicts, such as task delegation or role assignment, often carry personal connotations in terms of implied capabilities or respect within the group. For example, when a process conflict arises over the delegation of tasks, members who disagree with their task assignments may feel the task is below them and feel that being assigned the task is a personal insult. In this way, process conflicts may become highly personal and may have long term negative effects on group functioning.

Relationship conflicts are to be avoided if possible.

Relationship conflicts involve disagreements among group members about interpersonal issues, such as personality differences or differences in norms and values such as political or religious beliefs, hierarchy and rank order. These conflicts are most prevalent in high level teams, those who care about status and power. Relationship conflicts have generally been found to have large negative effects on both proximal and distal group outcomes. Disagreements about personal issues heighten member anxiety and often represent ego threats because the issues central to these conflicts are strongly intertwined with the self-concept. This ego threat often increases hostility among group members, which, in turn, makes these conflicts more difficult to manage, eroding group identification, trust and member commitment.

Most of these conflicts are not spoken up about directly, but indicated by indirect behaviours, choosing a process conflict to claim a choice responsibility to raise a status or via relationship conflicts, such as derogating someone to improve a position. These conflicts are very insidious, difficult to catch and difficult to resolve.

Cultural influences

Generally and for example, Europeans and moreso Americans, have a greater preference for addressing conflict with a competing style (Fu et al., 2007) and hold more positive beliefs about relationship conflicts compared to Korean and Chinese participants who generally score significantly higher on collectivism (Sanchez-Burks et al., 2008). Likewise, among cultures characterised by a long-term orientation, group members may have a greater preference for preserving good relationships for obtaining future rewards and therefore may be more willing to compromise and find a mutually beneficial solution than to win the conflict in the short term.

Finally, when the dominant values in a certain cultural context are relatively masculine, individuals may be more assertive, more rigid, and less caring for others during conflicts than among more feminine cultural contexts, in which individuals generally will be more cooperative in addressing conflicts.

Considerations

Train for Courageous Conversations – how about a Growth-shop or Team Coaching to help teams create better solutions through integrating divergent perspectives and sparking new ideas. By recognising and better investigating how members within the same team may come to view the same conflict in different manners, leaders may be able to better understand the nuances and dynamics of intragroup conflicts and leverage for the best outcome.

Maintain a constant flow of communication between the C-suite and employees, so that decisions at the top are translated throughout the levels of a company. A good corporate culture also encourages employee autonomy so they have the freedom and trust from management to make a decision about a problem in real time.

Learn how to craft and support psychological safety in your teams where employees believe that candor is expected and welcome and that team members are upskilled in the tools to engage in Courageous Conversations. Encouragement is not enough – Explore Courageous Conversations Growth-shops.

It isn’t enough to say you’ll be transparent and use conflict constructively. Without an approach determined in advance, less assertive voices won’t be heard when there is a disagreement, and a blanket commitment to debate ideas has the potential to be interpreted as a license to aggressively advocate for one’s position (rather than consent to engage in an open-minded, collaborative discussion).

If you’ve enjoyed reading my blog, please share with your network.

Please reach out, I’d love to be of help.

Wendy

Leave A Comment