Referring to his relationship with Monica Lewinsky, U.S. President Bill Clinton claimed “there is not a sexual relationship.” The Starr Commission later discovered that there “had been” a sexual relationship, but that it had ended months before Clinton’s interview with Jim Lehrer. During the interview, Clinton made a claim that was technically true by using the present tense word “is,” but his statement was intended to mislead: Jim Lehrer and many viewers inferred from Clinton’s response that he had not had a sexual relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Clinton’s claim is paltering: the active use of truthful statements to create a false impression.

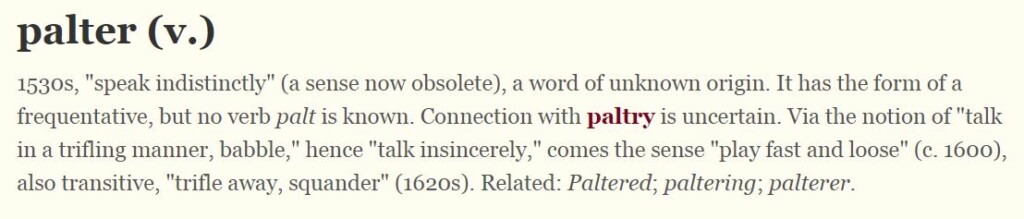

What are the origins of Paltering?

Very recently I uncovered an influencer in the whistleblowing space who has paltered their way into crafting a career by cynically appropriating a legitimate whistleblowers’ status and dressing up legitimate claims of an investigation and suspension by their employer as retaliation.

Here is an example taken from an interview with the person asserting their whistleblower status:

“..so it’s my experience, being part of this winning whistleblower group and the very negative effects it had on my career, coz I wasn’t really working for really prestigious organisation, I was rather proud being a Chief Executive of a charity….that being part of 3% is really not a very, it’s just, it didn’t excite me”

The only truthful part of these assertions is highlighted in red and acts as a convenient pinnacle between the lies. A crafty, subversive strategy in order to deceive.

After conducting a dispassionate due diligence on a number of these misleading statements I’ve been moved to explore the notion of paltering, the psychological drivers and the risks associated with the act and impact. What I learnt has helped me develop my understanding of how paltering contributes to both deception, fake information and conflict.

This is what I learnt.

Deception pervades human communication and interpersonal relationships; (Bok, 1978): DePaulo et al. (1996) found that people tell, on average, one or two lies per day. Though many lies are harmless, some are significant and consequential. That’s because our interactions are characterised by information dependence, and palterers exploit their counterparts by using deception.

Ommission, Commission and Paltering – what’s the difference?

- Lying by Commission is the active use of false statements

- Lying by Omission is the passive omission of relevant information. Lies by omission require targets to be complicit in the deception. For lies by omission to succeed, targets must hold and make known relevant mistaken beliefs and/or fail to ask relevant questions.

- Lying by Paltering ; though the underlying motivation to deceive a target may be the same as lying by commission and lying by omission, paltering is distinct from both. Paltering involves actively making truthful statement/s sandwiched between untruthful narratives. This is in order to create a mistaken impression. This is done in two different ways: prompted (by a question) and unprompted.

In some cases, deceiving targets in response to a direct question is perceived as more unethical than deceiving targets proactively.

This active form of deception harnesses conversational norms to shape false beliefs. Whilst both paltering and lies by commission communicate information that is relevant and informative, if targets were initially unsure or sceptical about the information being shared, paltering and lies by commission leads targets to form false beliefs.

Paltering promotes conflict, fuelled by self-serving interpretations, because while palterers focus on the veracity of their statements (“I told the truth”), listeners, observers, targets, focus on the misleading impression palters convey (“I was misled”) which leads them to perceive palters to be especially unethical.

Imagine this scenario: Over the last 10 years your sales have grown consistently, but next year you expect sales to be flat. If you are asked by your counterpart “How do you expect sales to be next year?” the response will be different depending on the type of deception:

- If you lie by commission, you might answer: “I expect sales to grow next year.” In this case, you are actively misleading your counterpart with false information.

- If you mislead with passive omission, you might remain silent if your counterpart says, “Since sales have gone up the last 10 years, I expect them to go up next year.” You are not actively correcting this false belief.

- If you mislead with paltering, you might say, “Well, as you know, over the last 10 years our sales have grown consistently.” This answer is technically true, but it doesn’t highlight your expectation that sales will be flat in the year ahead, and you are aware that it is likely to create the false impression by your counterpart that sales will grow.

The Risks to the Palterer and their Targets

By engaging in deception, individuals can often advance their economic interests, at least in the short-run. Deception, however, entails risks and costs. If discovered, reputations and long-term relationships will suffer, and the use of deception can trigger a psychological cost.

Palterers hold a mistaken mental model, failing to anticipate how negatively the targets of their palters will perceive them should they detect their deceit. By failing to anticipate palterings’ adverse consequences they fail to appreciate how paltering can escalate conflict. Prior work has shown that detected deception harms trust (Boles et al., 2000; Schweitzer, Hershey, & Bradlow, 2006) and increases retribution (Boles et al., 2000; Wang, Galinsky,& Murnighan, 2009)

We all strive to maintain a positive self concept (Adler, 1930; Allport, 1955; Kruger & Dunning, 1999) and the overt use of deception interferes with the palterers ability to preserve a moral self-image.

Compared with speakers or negotiators who tell the truth, speakers who palter are likely to claim additional value, but increase the likelihood of impasse and harm to their reputations.

Targets of paltering perceive paltering as far less ethical than palterers do. Whereas palterers are likely to focus on their use of truthful statements to justify the ethicality of their behaviour, targets focus on having been actively deceived and conclude that the use of paltering was unethical.

Paltering is a particularly effective form of deception because the use of active, truthful statements is likely to both distort a target’s beliefs and be very difficult to detect. Paltering deprives targets of complete and accurate information.

Psychological Drivers

A critical antecedent to engaging in deception is self-justification (Schweitzer & Hsee, 2002), and a related concern is the need to preserve one’s moral self-image. By using truthful, but misleading statements, those who palter may be able to effectively mislead others while justifying their behaviour and maintaining a positive self-image. Deceivers have abundant opportunities to palter, and paltering is relatively easy to justify.

Researchers, Todd Rogers, Richard Zeckhauser, Francesca Gino,and Michael I. Norton from Harvard University, and Maurice E. Schweitzer from University of Pennsylvania suggest that potential deceivers balance two competing concerns:

- how effective their deceit will be and

- how aversive the use of deception will be to their moral self-concept.

Deceivers who engage in paltering are likely to engage in motivated reasoning. Self-interest often guides how individuals perceive the morality of their own behaviour. Deceivers who palter, however, can focus on their use of truthful statements and discount the misleading consequences or attribute the misleading inference to the target (who should have paid closer attention to exactly what the deceiver was saying).

Suggestions

A stream of research has informed interventions to decrease the likelihood of being deceived, such as the important prescription to ask direct questions to curtail the risk of being deceived.

When individuals are not asked about a critical issue, they often omit information, but when asked a direct question they become far more likely to honestly reveal the critical information.

A powerful question also has the capacity to “travel well”—to spread beyond the place where it began into larger networks of conversation throughout an organization or a community. Questions that travel well are often the key to large-scale change.

There’s a strong compulsion to make people feel good by telling them what they want to hear, and for everyone to agree. That’s largely what gives us a sense of identity. There’s a strong tension here. Try to change the nature of conversation from a focus on what people value to one about actual consequences. When you talk about actual consequences, you’re forced into the weeds of what’s actually happening, which is a diversion from our normal focus on our feelings and what’s going on in our heads.

As we enter an era in which systemic issues often lie at the root of critical challenges, in which diverse perspectives are required for sustainable solutions, and in which cause-and-effect relationships are not immediately apparent, the capacity to raise penetrating questions that challenge current operating assumptions will be key to creating positive futures.

Do not be assuaged by responses that are not answers, by attempts to rationalize the answer or attempts to shame you as being the only one asking questions.

Train for Courageous Conversations – Leaders need the courage to admit they don’t have all the answers, courage to ask the right questions and courage to act on the information they uncover.

We’ve lost the art of discussion and with it the ability to find honest solutions. If the cost of maintaining a truth is greater than the ease of maintaining a lie, don’t be so sure that most people won’t be happy to help sustain a lie.

There are really only two options in a society as diverse, noisy and transparent as ours has become. We can either try to limit the noise by censoring, policing and muffling all those questions, terms and ideas that worry us. Or we can accept that the world we have created is cacophonous, and that the only consolation we might have is to train the next generation and ourselves to be able to pick out those words and ideas that we recognise to be true.

If you enjoyed reading my blog, please share it!