“It takes a team to pull off a good corporate fraud.” – Floyd Norris (New York Times, 2007)

Have you ever been in a position when someone in a position of seniority has offered you a commission or an inducement to influence your behaviour?

I have.

One year before blowing the whistle on corporate malfeasance at LeisureNet Ltd the joint CEOs called me into their offices and offered to settle a long outstanding personal loan I had. The conversation went like this: ‘Wendy, how long have you worked with us?’ I replied, with a certain amount of pride, that it had been eight years. ‘Wow! Really? Well, that deserves more than just a verbal acknowledgement. Rod and I have discussed your tenure and your loyalty and we’d like to settle your loan in it’s entirety.’ I can recall my sense of gratitude, of feeling worthy and safe and with emboldened loyalty I left their offices, cheque in hand.

The year was 1999 and whilst I was aware that other executive staff members had secured additional stock options, I was entirely satisfied that I had been unburdened by my loan.

By Mid-1999 LeisureNet had secured their largest offshore shareholder and with a deposit of £17,3million (ZAR 173 Million in 1999) in the bank, ‘locked door’ and ‘secret’ meetings with various significant players became the norm. One of these ‘locked door’ meetings was held with a senior partner of Deloitte, our external auditors. The Deloitte partner had had a long history with LeisureNet going back to the 1980s and I was somewhat surprised to learn that he subsequently resigned his partnership at Deloitte’s to join the LeisureNet Board and to operate as joint MD of our offshore subsidiary. The corridor talk was that he had been persuaded by a hefty bounty of stock options.

It was this negotiation that was forefront in my mind when I considered who to report legal and ethical breaches to in the following year, 2000. Having been met with purposeful obfuscation from my senior colleagues, my inclination was to report the breaches to Deloitte. However, I was stopped in my tracks, recalling the 1999 ‘locked door’ meeting, followed by the swift and unusual appointment of the senior partner of Deloitte to the LeisureNet Board.

It turns out I was right to be cautious.

The ‘sizeable contractual liabilities’ amounted to ZAR 900 million worth of leasehold liabilities which were left off the 1999 balance sheet.

Employees, the focus of this blog, are often asked to help implement corporate misconduct. Individual motives for facilitating misreporting include a sense of loyalty to the firm and to co-workers. The inducement is often framed within these borders, is nuanced and at best ambiguous.

Employees are more likely to co operate in wrongdoing if they gain financially from it. Even employees not directly involved with the wrongdoing may observe signs of misconduct and can decide whether to remain silent and allow the wrongdoing to continue or to blow the whistle and expose the misconduct. However, most remain silent to avoid being labelled a snitch. Those who do choose to blow the whistle do so to maintain personal integrity, to avoid complicity and to remove the public harm.

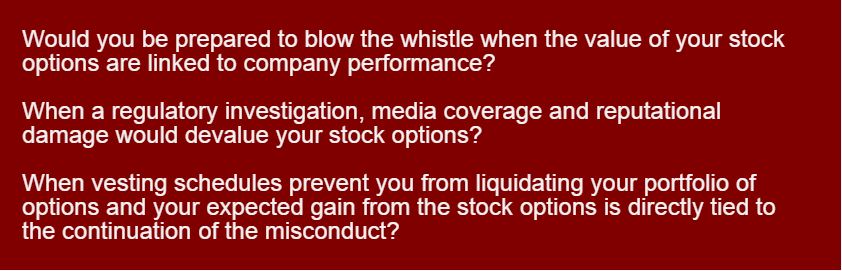

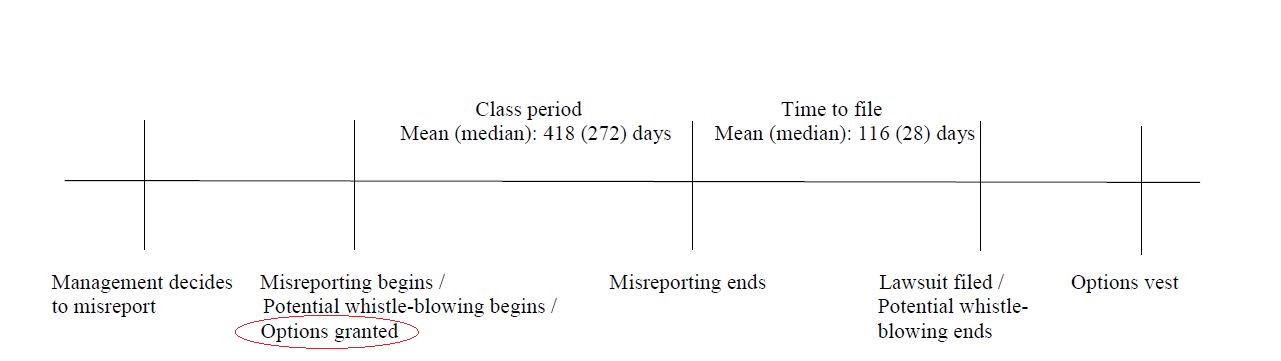

Recent research from Columbia Business School, Why are there so few Whistleblowers? indicates that organisations may grant stock options to employees to facilitate misreporting and to reduce the likelihood of employee whistleblowing. Employees with more stock options have a far greater incentive to support financial misrepresentation, either by facilitating the wrongdoing or by encouraging silence as we’ve seen in the LeisureNet scandal. Additionally, senior executives have the discretion to award larger option grants to the employees who are either perpetrating the wrongdoing or in a position to be able to discover it.

The value of an employee’s stock option portfolio is intrinsically tied to his or her decision to blow the whistle.

Just like the song from Mary Poppins ‘Just a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down’ , the stock options, and the repayment of my loan, are sweeteners to ease the intake of medicines such as silence and complicity.

The Push and the Pull

These recent findings might be of interest to regulators who design enforcement and whistleblowing programs. The Dodd-Frank Act encourages whistleblowing by offering rewards of up to 30{b7b8e70c88db6fe1c167eef14cad3ef391b44a4cec8172154df648b042cf3d33} of recovered damages and penalties, however this research suggests that organisations can counter this reward by offering financial incentives to discourage whistleblowing and to encourage silence about irregularities. Researchers found that organisations grant more stock options when involved in financial reporting violations, consistent with managements’ incentives to discourage employee whistleblowing.

These findings have important policy implications, given media reports that the SEC is investigating other ways in which firms subvert whistleblowing legislation, including confidentiality agreements in employment and severance contracts that prevent employees from contacting regulators or benefiting from government probes.

It would make for an interesting measure for regulators to evaluate whether an organisations’ compensation packages or employment and severance contracts were significantly altered after the implementation of Section 922 of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2011.

No matter what levers organisations may push or pull to dampen incidences of whistleblowing, a Courageous Conversation is required to ensure that you are not being commissioned, induced or quite frankly, bribed to implement or maintain misconduct.

Because I’ve been a user of Whistleblowing policy and processes, I have the customer in me. These insights and experiences allow me to build better training mechanisms.

Get in touch, I’d love to help

Leave A Comment