We are in the midst of a regulatory arms race to rein in corporate power.

Milton Friedman entered the stage during a slump in the economy in the 1970s, an ideal moment for him to influence the deregulation of the Reagan Era. Today, we find ourselves at another inflection point. Mounting global challenges, from climate change and shifting energy sources, to disruptive technologies and social media, and changing health and safety pressures call for us to re imagine how to anticipate and remedy bad practices that harm us and our world.

There’s been a new wave of thinking on compliance centres around corporate culture as the defining element of effectiveness. Responding to criticisms of compliance reviews and investigations as highly legalistic tools that fail to identify serious misconduct, this new wave of thinking seeks to broaden the reach beyond a sterile enforcement and deterrence mechanism.

The increasing importance of corporate culture in regulatory policy and companies’ growing engagement with ethics and integrity are definitely moving in a positive direction. In this blog I’d like to focus in on how the role of sustainability can help support this engagement.

ESG and ethics represent companies’ efforts to self-regulate in the wake of the realisation that a simple divide between legal and illegal activity is failing to serve shareholders’ and stakeholders’ interests.

At first glance, the role of sustainability may strike one as an unexpected choice for protecting a company against downside risk. Most people view sustainability as an effort to ensure that company decisions are in line with certain social or moral values. But, by operationalising their commitment to stakeholder values, many companies are also seeking to avert the reputational uproar, stock price drop and legal troubles following misconduct.

The values that ESG promote do not originate from an abstract moralistic philosophy of “doing the right thing,” nor are they dictated by a central standard-setter, as common with other industry self regulatory efforts. Rather, they arise following a wide-ranging consultation with stakeholders, who are better positioned to take notice of potentially catastrophic company operations.

ESG Adopts a Broader View of Harm than Compliance even when Protecting the Same Values

In this blog, I’ll start by situating ESG as an effort by companies to self-regulate their conduct, and compare it to compliance, the only other corporate function ensconced by law to rein in corporate misconduct. I’ll first explain why these two functions are comparable, and then explain why ESG is more effective as a tool for risk mitigation and for capturing those voices speaking up, in comparison to compliance.

Sustainability pushes companies to think about concerns that might be currently unregulated but invoke values that law often protects.

There’s an institutional affinity between sustainability and compliance, underscoring why comparing the roles makes sense. Even though, quite often, the legal, compliance, and ESG departments work together to advance future policies, when considering how to best defend and promote a shared value, compliance’s focus is much narrower than ESG’s.

Because of its focus on legal risk, compliance is backwards looking, reflecting conceptions of harm as they stood at the time of enactment. Additionally, the true extent of corporate misconduct may not become publicly known until much later, when the impetus for reform is gone. In the same vein, Whistleblowing is about ‘the time after’ and fits into an ethical fix-it framework, whist learning to speak and listen up via training for Courageous Conversations is about ‘the time before’ and protects a company from downside risk, blindspots and slippery slopes.

What rules prohibit depends on the vicissitudes of our legislative and rule-making systems

Compliance remains tethered to statutory and regulatory definitions of appropriate conduct, harm and liability. In contrast, the stakeholders that populate ESG’s information gathering efforts focus on negative developments on the ground, regardless of whether they are punishable by law. This voluntary commitment, often through Courageous Conversations, is outside of the law and allows a company to constantly redefine. The associated flexibility is particularly valuable because, unlike the policymakers that set compliance’s goals, companies have access to far superior information sources that can detect harm and more imaginative solutions for anticipating or remedying it. Besides, policymaking is a time-consuming process, which requires generating public support, building political alliances, lobbying and counter lobbying. It takes time until the real impact of any problem is fully revealed, which touches a broad enough base of voters to spur lawmakers into action. In contrast, sustainability teams are well placed to grasp the impact of company choices on a broader set of constituents and even to gauge public reaction and appetite.

Compliance is therefore confined to targeting legal risk, rather than business risk. This is a possible reason for whistleblowing falling under employment legislation and being managed by compliance professionals. As a result I’ve found many companies adopting whitsteblowing hotlines and embedding processes as mini litigation defence centres only. Generally, compliance officers look to the law in order to fulfil obligations and identify elements of violations, without much leeway for company by company variation. This legalistic approach is even more pronounced in specialised compliance regimes, such as anti-money laundering, which do not only define substantive rules, but also put in place specific compliance procedures in furtherance of these rules. Often, new practices develop to take advantage of regulatory loopholes, or simply to stay clear of legal boundaries. Although these practices do not violate any laws, they sometimes come to present a challenge to the underlying value that our legal system is trying to serve. See my blog ‘In all the legal manoeuvring something gets lost; the truth’

Compliance puts employees and managers on the spot and threatens sanctions, often leading managers to conceal or ignore misconduct. In contrast, sustainability offers a new, optimistic vision for the future without lingering on the past, encouraging everyone to enter afresh into new commitments. Well-documented agency conflicts that often undermine compliance efforts are less pronounced in sustainability’s case. Moreover, ESG initiatives manifest the company’s credible commitment to stakeholder concerns which help establish trust that can come in handy if risks materialises. Let’s look at gender equality in the workplace as an example. Compliance focuses on sexual harassment and discrimination, while sustainability looks at issues such as women’s representation in leadership roles. In this particular example, the deeper motives are shared but through different lenses and at different times.

If sustainability leaders are seeking to identify issues that may not be on the company’s radar by turning to external stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, communities, civil society groups, NGOs, the media, and academia ie: what’s considered the ‘public’s interest’, could these leaders also harness and nurture the voices of those speaking up in the public’s’ interest? See my previous blog “What’s the link between an Organisations’ Purpose and Speaking Out in the Public Interest?”

Information Gathering

The sustainability role summons a very different set of forces to the compliance role. What solidifies ESG is not unity of subject-matter, but the common process of consulting stakeholders and operationalising feedback into achievable and measurable goals for the company. ESG gathers information from stakeholders to help companies mitigate risks.

Watch the video below which I’ve broken into punchy, short chapters, with lots of nuggets where Rob Chesnut, Ex Chief Ethics Officer of Airbnb, identifies supporting reasons to consider ESG as a more helpful informational function to capture the voices of those speaking up in the Public’s Interest

Broadly, the ESG process unfolds in three distinct stages. In the first stage, known as “materiality assessment,” sustainability officers invite internal and external stakeholders to provide input. Aligned with acknowledgement that employees are the first to spot most irregularity, sustainability officers typically begin with employees. This is a significant first step, aligned with research in the whistleblowing space, which identifies employees as the first ones to observe a major threat to the company’s core business. That’s because employees are in direct contact with any harm potentially caused. The difference in gathering further information however differs from an investigation lens via compliance and in-house counsel to an information gathering lens via the sustainability role. One significant difference is employees being interviewed outside the corporate hierarchy in order to identify concerns that may not reach the executive level.

Inviting stakeholders to sit across the table from company officers is a bold move. Some may see themselves as the nemesis of large corporations and would mobilise to fight against business interests. Their opposition is often rooted in their perception of “big business” as a destructive force that often disregards its impact on society. Precisely for this reason, their feedback helps sustainability officers identify concerns whose weight company management might fail to grasp. Often stakeholders are seen by ESG not only as watchdogs, but also as partners to their companies, inviting them to sit across the table and share their concerns. Utilising this informal mechanism allows sustainability officers to capture titbits of data that could affect the company’s profile and reputation, or societal trends that might emerge into risks. For instance, at one company researchers visited, they discovered a group of interns working in an open office with large screens, monitoring what the youth in various markets were saying about the company on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms.

To understand ESG’s strength as an information collection tool, we need to explore why these disparate actors are willing to abandon deep rooted fears and long-held biases and share information with ESG freely, or at least more willingly compared to other forums.

First, ESG’s forward-looking perspective and inclusivity helps stakeholders overcome the threat of liability and retaliation that often undermines compliance. Where compliance seeks to sanction and deter, ESG seeks to reconcile and inspire. Second, ESG helps establish trust between the company and its stakeholders. Through the ESG process, information flows in both directions. By showing interest and undertaking initiatives, the company also communicates to stakeholders its commitment to shared values, to be proven in practice through its initiatives. Stakeholders are therefore more likely to trust a company with a more successful ESG function.

For any company employee caught misbehaving, and for any manager found to turn a blind eye or simply let her guard down, an internal compliance investigation is a stressful process. Often, the risk of legal liability looms large, forcing the main culprits behind a wall of self-protection. Regardless of legal sanctions, whistleblowers reporting misconduct may lose their job and suffer a career setback, or worse. Even without being directly targeted, those participating in the process may come to perceive it as strict, bureaucratic and unyielding. Compliance produces a written record often synthesised in a report, which can be unearthed in inopportune moments. Under such circumstances, blowing the whistle is not be the easiest choice, countermanded by natural psychological conflict. It is not surprising that employee cooperation with compliance staff has never been entirely smooth.

Even from the board itself, compliance often elicits a mix of eagerness and trepidation. Corporate boards have authorised and overseen a huge expansion of compliance departments in an effort to rein in corporate misconduct and satisfy their fiduciary duties. But compliance reports that raise red flags informing the board about violations are an essential link in establishing bad faith, if the board subsequently fails to address these violations adequately. Practically, the board may wish to “never have known” about illegal activity, because then it risks seeing its reactions challenged in court. Under such threat, boards may choose to stay aloof and limit their exposure to challenging reports, rather than step up and fix the problem. Ultimately, compliance is a mechanism intended to deter violations through monitoring, and to impose sanctions in a quasi-disciplinary setting when violations are caught.

Deterrence and sanctioning have an important role to play in fighting corporate wrongdoing. But clearly, they are intended to be feared and not celebrated. This conundrum of risk monitoring and liability eases considerably under the umbrella of sustainability. Although sustainability evolves around issues of key legal interest, it employs a non-confrontational approach and therefore is a sound partner to the skill of Courageous Conversations BEFORE Whistleblowing. Research by Stavros Gadinis & Amelia Miazad discovered that employees participating in sustainability discussions are more forthcoming about issues that threaten the company.

Sustainability does not point the finger toward specific problematic individuals, but instead deals in broader terms, emphasising culture, values, and relationships. It does not get triggered by a mandate to penalise a violation, but by a desire to uphold a value, nurturing and harnessing our self-concepts as good, moral people. It does not scrutinise the past, seeking to sanction mistakes, but looks to the future, helping the company evolve. The outcome of a sustainability initiative is not severance or lawsuit, but a transformed product, process, or corporate culture.

Sustainability may replace previous practices, but it does not directly criticise the employees who followed and tolerated them, making it easier for all to adopt and adapt. Of course, not all may be amenable to change, and sometimes changing established patterns of behaviour may prove an uphill battle. But the mere fact that sustainability focuses on company-wide initiatives rather than individuals’ own failures removes a point of contention and helps push reforms forward. Sustainability brings with it a promise for self-improvement, a recognition that, regardless of how we did business in the past, we can do better from now on.

As an example, to insulate participants from fear of retaliation or other legal entanglements and invite uninhibited information flow, Airbnb redesigned its approach to compliance. As seen in the video for my blog, its general counsel, Rob Chesnut, invested in developing direct communication with employees which emphasised proactive conversations and risk prevention, as opposed to only reactive investigations and sanctions. In an unusual commitment for such a high-ranking executive, he personally led an orientation session for new Airbnb employees each week to champion the company’s values and strengthen connections. He based his sweeping and non-hierarchical approach not on the concept of law, which he believed would alienate people, but on the concept of practical integrity. This resonated with employees. Go here to explore Rob’s book Intentional Integrity.

While conventional corporate governance tools like compliance tend to antagonise internal stakeholders and exclude external ones, ESG encourages an iterative process of negotiation that helps boards solidify their response and build ties. I therefore advocate that policy makers and courts recognise ESG as the essential role to capture the voices and messages of those speaking up.

ESG Addresses Social or Moral Challenges Even when No Laws Are Violated

ESG leaders are not interested in how employees perform their mandated obligations, but in problems that the rulebook fails to capture. ESG officers interview company employees across the corporate hierarchy as a matter of course and a change in process would allow the sustainability team to identify inconsistencies between commitments made at headquarters and what is happening on the ground, in addition to identifying new risks that managers may not have fully comprehended.

The difference between the compliance and ESG approaches can help explain why companies hit by compliance failures turn to ESG in an effort to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Indeed, in some cases, companies have turned to sustainability initiatives at the urging of in-house lawyers. As an example, Wynn Hotels, whose CEO and founder resigned amidst a widely publicised sexual harassment scandal, recruited new female directors and introduced new communication channels between these directors and employees. Collectively branded the “Women’s Leadership Forum,” these communication channels included town hall meetings, events and fireside chats between directors and employees outside the typical corporate reporting hierarchy or the compliance apparatus. But this approach is hardly unique to companies emerging from scandal. LinkedIn’s CEO, Jeff Weiner, refers to his own style of leadership as “compassionate management,” encouraging employees to “speak up” and “address pain points” in town hall meetings.

Openness is a new operational reality

The informational advantage enjoyed by company ESG officers over policymakers is even starker when business developments generate new social challenges that fall outside the current ambit of the law. Companies are needing to adapt to an information environment that is continually being transformed. Notwithstanding the plethora of new tools to track and monitor workers, suppliers and customers, the efficacy of top-down efforts to control information flows has collapsed. Growing public scepticism of business has rendered one-way communication less effective. Senior leadership’s effective power and control is fading and public accountability increasing. Maintaining a good reputation today starts with the presumption that everything a company says or does could become public knowledge. The explosion of social media has driven millions of users to voluntarily relinquish their private information online and only slowly come to grips with the myriad ways in which this can be exploited. See more on Open Dialogue here.

ESG’s informational advantage is particularly valuable if a crisis hits a company. Faced by narratives of unsuspected victims suffering harm they did not bargain for, a company can hardly protect itself by pointing that it did not actually violate any laws. That no longer washes. The absence of legal obligations, can turn into a drawback when the true extent of the harm is revealed unless a company has a clear-eyed perspective on the interests of potentially affected stakeholders, and has developed decisive and proactive action to protect them in the long run. The ESG function is well-equipped to serve this role.

The most recent Facebook/Cambridge Analytica debacle exemplifies a profound corporate crisis, unabated by the absence of any primary legal violations, that a robust sustainability function could have helped to avoid. Even though Facebook could claim to have obtained the contractual consent of its users for exploiting their data, it faced accusations that its practices violated users’ privacy. Mark Zuckerberg found himself the unwilling protagonist of a ritualistic congressional hearing, culminating in a humbling apology to stem the slide of the company’s share price. He repeated time and again that no laws were violated, but shareholders could not have been happy with how the debacle unfolded within the company. Yet, details of the problem were well-known among employees, who were concerned about the company’s treatment of its users. Alex Stamos, the company’s Chief Security Officer, had spotted the problem months ago and was ringing alarm bells, but Cheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer, chose not to heed these warnings, misjudging users’ reaction if the problem was revealed. As Facebook’s former vice president for global communications, marketing and public policy recently conceded, “[w]e failed to look and try to imagine what was hiding behind corners.”

ESG has grown into a corporate function that subjects any aspect of corporate operations to a test of moral rectitude and social equitableness. It feels like a good fit to support people speaking up in the public interest.

“Doing well by doing good” helps advance ESG from the corporate philanthropy pigeonhole into a core-business mindset and has shown great momentum. Can we surf that momentum to explore the willingness to transfer the custodianship of whistleblowing and speaking up from compliance to sustainability?

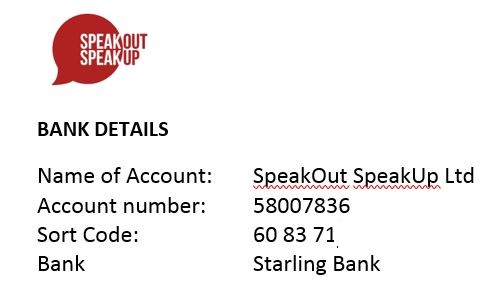

It’s been a tough four months. If you enjoy my work and get value from my messaging and blogs, please consider donating to SpeakOut SpeakUp Ltd to help me sustain my work. Thank you!

Leave A Comment