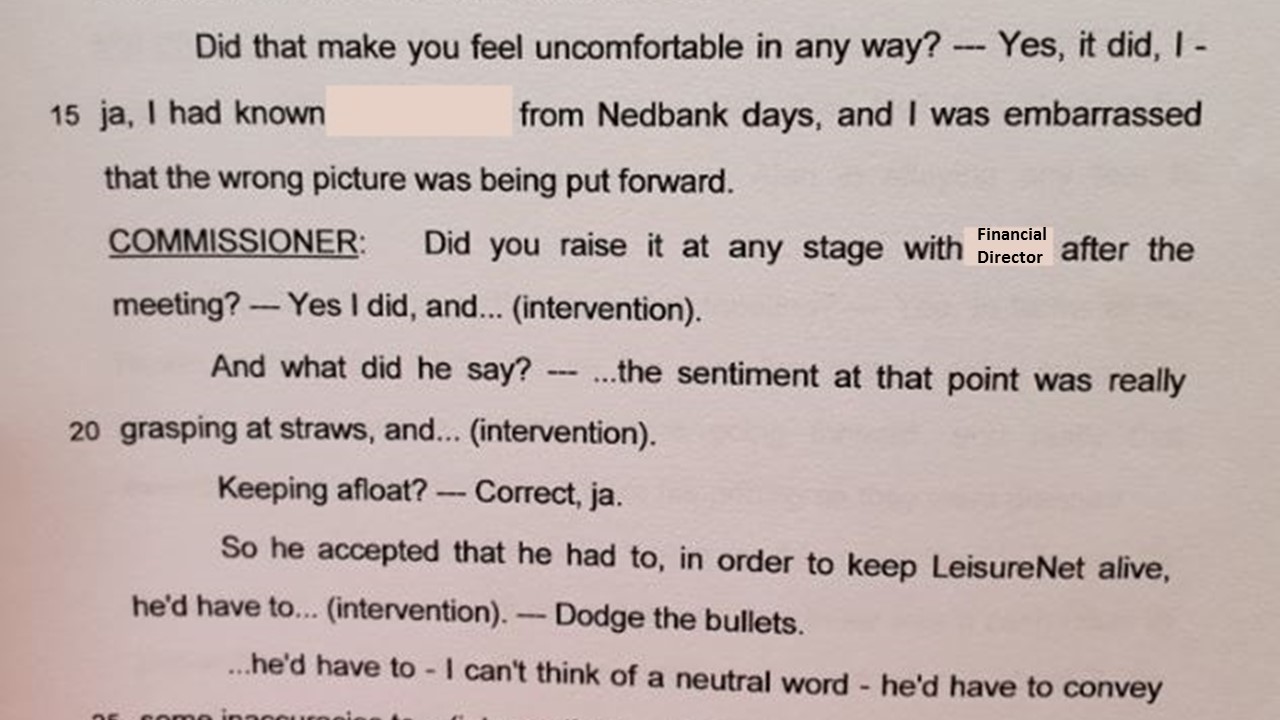

Sitting around the Boardroom table at the corporation I blew the whistle on, LeisureNet Ltd, I heard one of our directors blatantly lying to Barclays bank about our financial position. This was to persuade Barclays to provide additional lending, to keep our organisation afloat. As you can see from this snippet taken from my testimony in the Cape High Court, I felt embarrassed and made attempts to raise my concerns to the director after the meeting. My expressed disagreement and sentiment weren’t listened to and Barclays went ahead and provided an additional £10 million pounds of finance to LeisureNet Ltd. The outcome? Two months later, when I blew the whistle, Barclays bank lost every cent of this loan and I was left with the shame and regret of not being heard.

Why didn’t the Director listen to me?

Disagreement is a key feature of social life, permeating organisations, families, friendships and crisis responses. We regularly find ourselves engaging with people whose fundamental beliefs and core values differ from our own. One common response is to try to convince them to abandon their point of view in favour of ours. But that approach can backfire, leading to unproductive conflict especially when individuals have interdependent goals that are more important than resolving the disagreement itself.

Conversation is a fundamental human experience that is necessary to pursue intrapersonal and interpersonal goals across myriad contexts, relationships, and modes of communication. We converse with others to learn what they know—their information, stories, preferences, ideas, thoughts, and feelings—as well as to share what we know while managing others’ perceptions of us. The two central goals of conversation are information exchange and impression management.

Watch the .16second video of Trump below appearing to demonstrate a willingness to be receptive, to Listen-up. That is, until he threw in an interpersonal insult. How receptive would you feel after that sucker-punch?

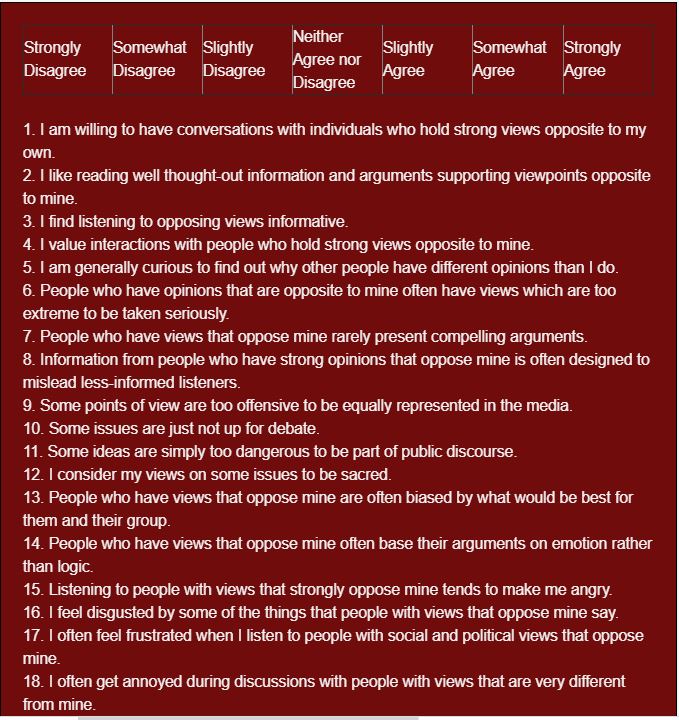

How might you fare? Imagine you are at a similar high-level meeting as I had attended, and a senior executive starts leading the meeting down a nefarious route which you strongly disagree with. Or at a family dinner your ”ill informed” uncle starts going off about his views regarding immigration, which you strongly disagree with. Do you find yourself changing the television channel when a political candidate you oppose begins to speak? Do you remain in the room when a colleague begins to discuss their views on abolishing the death penalty, legalising same-sex marriage, legalising a market for human organs or the regulation of firearms?

| What came up for you? Did you feel as though you’d be positively open to aspects of being exposed to opposing views,such as empathising with different perspectives or satisfying curiosity? And/or do you hold a set of beliefs about the sacred nature of some issues, avoiding disagreement because you believe that particular issues are not subject to debate? Did you identify any rising negative emotions, such as anger, disgust, frustration? Individuals can frequently be heard praising others for being “good listeners” or condemning them as being “closed-minded.” Clearly, our perception of others’ receptiveness is an important dimension of social judgment, especially in contexts rife with disagreement. Recent research from Michael Yeomans, Julia Minson, Hanne Collins,Frances Chen and Francesca Gino indicate that people may hold their own behaviour and others’ behaviour to different standards, resulting in the slow escalation of receptiveness and allowing people to attribute blame for conflict to other people. There are in fact distinct and consistent features that lead people to believe they have been receptive (even when they had not come across as such). In the aforementioned study, participants mainly gave themselves credit for formalities (e.g., using titles, expressing gratitude, absence of swearing) rather than on demonstrable engagement with their partners’ point of view. Could it be that we have a broken mental model of receptiveness – that we may not know how receptively we are perceived, and therefore might not know how to change our communicative behaviour to appear more receptive? The Receptiveness of Listening-Up The benefits of receptive listening-up have been well documented. Employees who feel that their boss listens to them experience less emotional exhaustion and report being more willing to stay in their positions (Lloyd, Boer, Keller, & Voelpel, 2015); and open-mindedness among supervisors and employees leads to more efficient solutions to workplace conflict communicating. Listening-Up receptiveness is an effortful strategy even when one has every intention of being so. It’s also a learnt skill which pays dividends. Individuals participating in the research who were rated as more receptive were also perceived as more desirable team members, were seen as having better professional judgment, and were rated as more desirable organisational representatives. Words Matter Receptiveness is partly hampered by an individuals’ inability to clearly communicate their willingness to thoughtfully engage with their conversational partners’ opposing views and by the words they use. Research by Huang, Yeomans, Brooks, Minson, & Gino, 2017; Jeong, Minson, Yeomans and Gino, 2019, has shown that the language expressed in conversation can be treated as a behavioural indicator of interpersonal goal pursuits. This is important. When one individual does signal their willingness to have a thoughtful and respectful conversation, the words they use to communicate that willingness ultimately determines whether their partner does or does not accurately interpret their intentions. This interpretation in turn affects the partner’s reciprocal behaviour toward the speaker, both in the current conversation and in the future. Conversational receptiveness involves using language that signals a person is truly interested in another’s perspective. When individuals appear receptive in conversation, others find their arguments to be more persuasive. And receptive language is contagious: it makes those people with whom one disagrees with more receptive in return. People also like others more and are more interested in partnering with them when they seem receptive. Disagreements that may have spiraled into heated conflicts instead lead to conflict resolution. Interpersonal conflicts of all kinds – in organisations, in politics, in families – often include parties who assert that the other side has not listened to them carefully, considered their arguments thoughtfully and evaluated their position in a fair-minded way. The belief that the ‘other side’ is failing to be sufficiently open to or respectful of one’s views features prominently in the clinical psychology literature on conflict. Balanced and thoughtful consideration of opposing perspectives is the exception rather than the rule. People often seem unable or unwilling to consider opposing views with the same level of tolerance as they afford to views that echo their own (Fernbach, Rogers, Fox & Sloman, 2013; Krosnick, 1988; Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979; Pronin, Gilovich, & Ross, 2004). Conflict can therefore be perpetuated by the opposing parties’ reluctance to expose themselves to each other’s arguments and evaluate them in a thoughtful and fair-minded manner People know receptiveness when they see it. Humans, however, are not able to pinpoint which words and phrases make a piece of text feel more or less receptive. What is Listening-Up Receptiveness? Receptiveness is a willingness to expose oneself to, and to thoughtfully and fairly consider, the opposing views of others. Most of us can readily recall a specific instance when a conversation partner with an opposing viewpoint listened to our arguments thoughtfully, seemingly considering the proffered information, and asked follow-up questions suggesting genuine curiosity and a desire to understand. Such experiences are memorable in part because they are rare. When the issue at hand is a deeply held, identity-relevant attitude—as may be the case in many social, political, or international conflicts—disputants rarely display a willingness to even-handedly consider arguments for both sides of the issue. Instead, they selectively seek out, attend to and preferentially process information that supports their prior opinions. This locks us into an echo chamber where we tighten our firm grip on our strongly held beliefs, attributing any disagreement to ignorance, bias, or malevolence on the part of the disagreeing other, readily dismissing any new considerations. This aligns with research on the phenomenon of naïve realism which indicates that even after having been exposed to and having considered opposing views, some individuals still find ways to banish the undesirable evidence from their minds on the grounds that it is inferior or irrelevant. The researchers theorise that the biases at major stages of information processing including (1) information seeking, (2) information recall, and (3) information evaluation, covary as a function of an individual’s level of receptiveness. The pathway to growth and development is when individuals are skilled up to actively communicate their willingness to expose themselves to opposing views and to process information more thoroughly and thoughtfully. By doing so they avoid the temptation to consider or dismiss the information based simply on whether it supports or opposes their beliefs. Why does Listening-Up Receptiveness matter? Organisations depend on active and healthy conversations among diverse perspectives for making decisions and giving voice to underrepresented views. Where conflict management is endemic to productivity, conversational receptiveness at the beginning of a conversation forestalls conflict escalation at the end. This is one of the reasons I advocate and train for Courageous Conversations BEFORE the need for a whistleblower. As opposed to encouraging individuals to blow the whistle on suspected malfeasance, engaging in a Courageous Conversation as a first step allows a change of attitude towards listening-up receptiveness. Additionally and amongst many other positive outcomes, a Courageous Conversation avoids the legal costs of whistleblowing, regulatory scrutiny, conflict spirals that harm relationships and spill over into other relationships, and can be revisited in a circular fashion, extending beyond a single conversation, disclosure or report. Listen-up receptiveness can contribute to the “subjective value” eg.; positive emotions and perceptions relating to one’s debate or negotiation counterpart during a negotiation or in a conflictual setting. This in turn predicts positive, long term outcomes. Individuals may hear the other side’s arguments, consider them thoughtfully, and come to the conclusion that although the arguments on the other side are of a nature that are reasonable and ones that moral people could make, the arguments on their own side are either more weighty, more numerous, or more plausible. Reasonable individuals can then decide to revisit the Courageous Conversation or even decide to retain their prior attitudes and “agree to disagree.” Individuals high in receptiveness are 1. More willing to seek out belief-disconfirming information (i.e., demonstrate less “selective exposure”); 2. Individuals high in receptiveness exposed to belief-disconfirming information pay more attention to it. 3. Receptive individuals offer assessments of that information that appear less biased by their prior beliefs. Situational versus Character Receptiveness An individual’s level of receptiveness can vary with the situation. For example, people may be less receptive when confronted with contrary views that assail their basic values or their desire to believe in a certain state of the world. (Tetlock, 1986 + Dawson, Gilovich, & Regan, 2002). Similarly, people may be less receptive when experiencing emotions high in certainty, such as anger or pride. Considerations Upskill and provide training for Courageous Conversations in order to nurture the ability for people to move away from truth assumptions, freeing them to shift their purpose from ‘proving we are right’ to understanding the perceptions, interpretations and values on both sides; Learn the language that is the Recipe for Receptiveness via Courageous Conversation training; Understand the difference between intention and the impact an opposing opinion might have on you; Appreciate that wisdom comes from rejecting the feeling of knowing; To do good work you need a brain that can go anywhere. And you especially need a brain that’s in the habit of going where it’s not supposed to. Choose to expose yourself to a wider variety of views, and/or to even more selectively curate them; Don’t run from tension. Courage develops from the rope of experience that is thrown to us – grab that rope. In closing, it’s true to say that when words do not align with actions, receptive language may seem like cheap talk. However, receptiveness a crucial step toward relational repair after a conflict episode. This is particularly relevant when the disagreement is asymmetric – for example, in customer service or human resources mediation, where one person involved in the disagreement is acting on behalf of an organisation. If you enjoyed reading my blog, please share it with your network. And get in touch, I’d love to be of help. |

Leave A Comment