There has been appropriate outrage at your actions in seeking to unmask a whistleblower at Barclays Bank. The angry rhetoric is a reaction to the misalignment with what the ‘Barclays Way Code of Conduct’ invites workers to do to raise concerns and your actual response.

You hold a powerful position, you should know better.

The Barclays Way Code of Conduct:

(Reader Caution: before you dismiss this as relating to ‘other’ organisations only, you will possibly be able to identify some of same language utilised in your own invitations to staff on how to raise concerns.)

Should you have known better? You’re human, right?

You’re suffering from Pavlovian messenger syndrome and you’re not alone. Before I move on, let’s re visit history’s’ original messengers. In the book Plutarch’s Lives we find that the Roman messenger who gave notice of Lucullus’ coming so displeased Tigranes, King of Armenia, that he had the messengers’ head cut off. As a result, and henceforth, no other person dared to bring further information. The outcome being that without any intelligence at all, Tigranes sat while war was already blazing around him, giving ear only to those who flattered him.

The number of times this happens in organisational contexts is countless.

Watch .20seconds of a clip from TV show Billions, when the CEO discovers a staff member has been asking too many uncomfortable questions, speaking up.

In the above clip ‘messenger’ is changed to ‘quizzling’ but the attitude towards both labels remains constant – outrage, with a hunters’ mentality.

Further tales abound such as the Ancient Greek story of Antigone, by the writer Sophocles where mention is made that “No one loves the messenger who brings bad news”. Later, this bias was used by Shakespeare in Henry IV, part 2 (1598) and in Antony and Cleopatra; when told Antony had married someone else, Cleopatra threatens to treat the messenger’s eyes as balls, eliciting the response ‘gracious madam, I that do bring the news made not the match’.

There’s a theme here and it’s a theme about human behaviour and our inbuilt response to news that threatens our status quo, our own sense of self efficacy and self image, resulting in ‘deaf ear syndrome’ or worse, conditioned Pavlovian messenger syndrome.

Constructive criticism and negative feedback can be one of life’s great gifts and an engine for improvement, however, before we can benefit from it, we must be prepared that some of it will hurt. If we are not at least implicitly aware of the conditioning phenomena and invite people to tell us what we don’t want to hear, we may develop a certain disliking to those delivering the news.

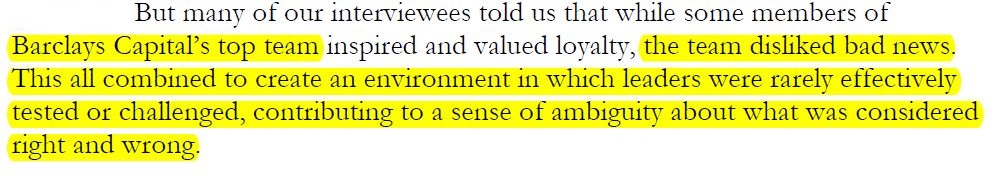

Mr Staley, I want to draw you back to the Salz Review, an independent review of Barclays’ Business Practices, prepared in 2013. Within this review there are a multitude of pointers to the difficulty of staff attempting to speak up the chain of command. This one in particular grabbed my attention at the time because of it’s potential for long term negative reach.

2013 to 2017, four years and not a lot appears to have changed – it is this that speaks to the conditioning phenomena of the Pavlovian messenger syndrome.

There is much work to be done and damage to be undone.

Whilst the ‘Barclays Way Code of Conduct’ is helpful in providing handrails to disclosure, it does very little to encourage staff to speak up or out. It’s mere scaffolding.

Because I’ve been a corporate whistleblower who successfully secured justice against corruption, I’ve been a user of whistleblowing policies and processes and have the customer in me. I’d therefore like to share some insights on what works:

You can encourage people to speak up, tell them ‘if you see something, say something’ but what speaks louder than these narratives is the response that you demonstrate when someone does speak up. Your response builds the perception of safety or unsafety and fuels courage or fear.

Listen Up: Learn to manage your own defensiveness to avoid Deaf Ear Syndrome

Question your willingness and ability to hear certain voices and not others. Begin by making a habit of second-guessing your enthusiasms as well as your antipathies since both will cloud your judgement.

Don’t take your position of power for granted. As a member of a privileged in-group, remember what it is like to be in the less privileged out-group. As a leader you need to solicit information.

Soliciting information is not repeating the mantra of “My door is always open.” This type of narrative contains a number of assumptions. First, people should meet you on your territory, rather than the other way around. Second, you have the luxury of a door. Third, you can choose when to close or open it.

Remove barriers to speaking up internally by targeting underlying employee perceptions.

Learnt associations do not serve us and our relationships well. Keep in mind that: (1) people are neither good nor bad because we associate something positive or negative to them; (2) bad news should be sought immediately and your reaction to it will dictate how much of it you hear.

If people tell you what you really don’t want to hear — what’s unpleasant —there’s an almost automatic reaction of antipathy. You have to train yourself out of it. It isn’t foredestined that you have to be this way. But you will tend to be this way if you don’t think about it and train for change.

Awareness and understanding may serve as good first steps. Yet, even when taken together they may not be sufficient to unlearn some of the more stubborn associations.

You may be interested in my training mechanism for Courageous Conversations where participants learn to interrupt their own unhelpful patterns as well as unhealthy organisational patterns to create adaptive, self-correcting cultures of behavioural integrity, success and innovation. Speaking Up internally becomes normalised, preventing a whistleblower entering the scene.

Sent in the spirit of service; please get in touch, I’d love to help

Leave A Comment