A CEO transcript of a conference call to Investors post a Merger and Acquisition:

|

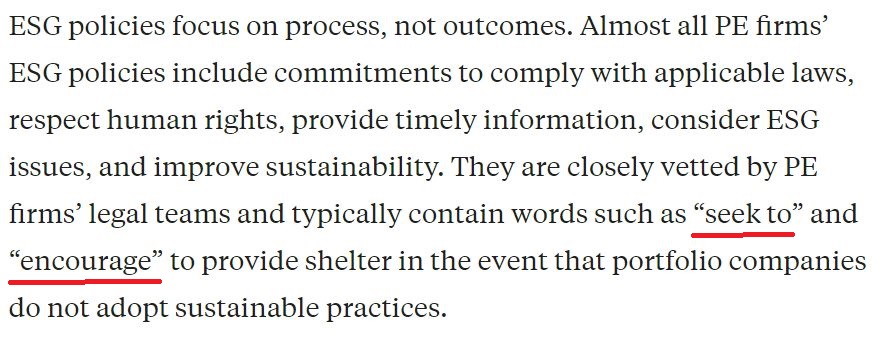

This, of course is not surprising and through the bullshit legal terms of ‘seek to’ and ‘encourage’, organisation’s are avoiding accountability for their claims.

Words matter. For example the social practice of bullshitting was found in a study of health and safety practices in a Norwegian offshore oil industry. The study found that many of the onshore agencies were adept users of the word ‘resilience’. Researchers noticed that onshore staff such as managers from a large oil company and government officials were adept at speaking at length about resilience, but rarely would they be specific about what they actually meant. This meant the concept was essentially ‘unclarifiable’ and could be applied to almost any aspects of the shipping operation. The offshore operational staff became sceptical and indifferent about ‘resilience’. The offshore staff could talk about resilience when they were expected to (for instance, when a safety inspector arrived), but they didn’t seriously believe in it. One ship captain described resilience talk as ‘toilet paper’ which he only used to ‘cover my arse’.

Offshore operatives used the language of resilience as a kind of game they were expected to play if they wanted to legitimate their work in the eyes of distant bureaucratic bodies who would infrequently take an interest in them.

How does Bullshit manifest and Evolve?

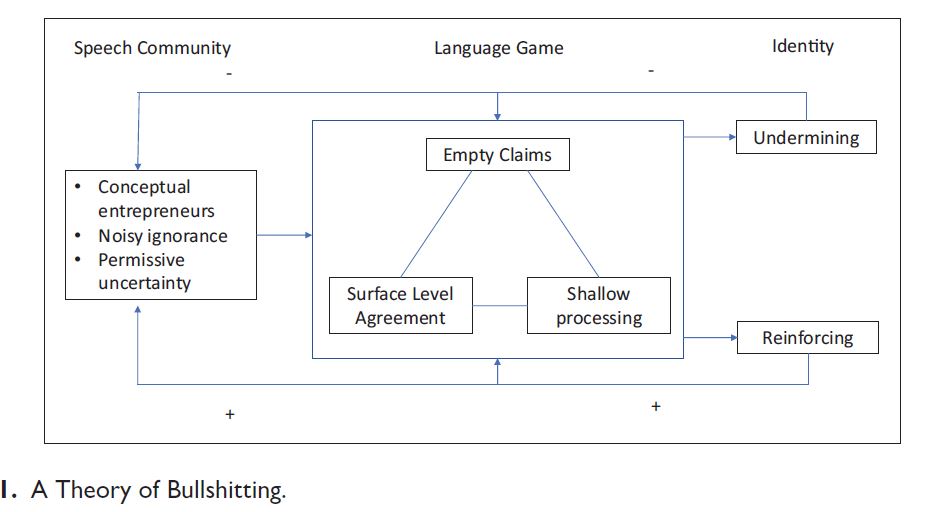

Let’s begin with the Speech Community, as seen in the figure above. the Speech Community is recognised by ‘any human aggregate characterised by regular and frequent interaction by means of a shared body of verbal signs”.

Who and What makes up this Speech Community?

- Conceptual entrepreneurs. Many conceptual entrepreneurs operate in the management ideas industry. This is a sector made up of consultants, gurus, thought leaders, publishers and some academics. This group is variable and consequently some of the conceptual entrepreneurs seeking to peddle their wares in the management ideas industry are bullshit merchants.

- Noisy ignorance. This is when people lack knowledge about an issue yet still feel compelled to talk about it. Noisy ignorance is mainly due to a lack of understanding or experience concerning the issues being discussed. Often that ignorance has been strategically cultivated such as, in some cases, where individuals deliberately avoid gathering information or knowledge about an issue. In other cases, noisy ignorance is created by knowledge asymmetries where one party knows much more about a particular issue than another. When anyone is relatively ignorant about an issue, they do not have the wider background knowledge in order to compare new claims. Nor do they have an understanding of the right questions they might ask or the humility to do so.

- Permissive uncertainty. When faced with a challenging issue such as a significant and unexpected challenge, some organisations experience high levels of uncertainty but also find that different kinds of experts claim ownership over the problem This can create experimentation, participation and dialogue. But equally, it can create multiple failures, conflict and drift. Under these circumstances, a greater sense of confusion can well up and an ‘anything goes’ approach takes hold. I expect to observe a lot of this as the EU Whistleblowing directive is rolled out and regulation around organisations’ ESG and non financial disclosures is delivered.

The community within the Speech bubble leads to –

Language Games

Within the context of organisations, language games can include repeating the ideas of management gurus, developing strategic plans to engage in competitive wars, interacting in an online chat group or engaging in an inquiry following a scandal.

To this list, I would add bullshitting.

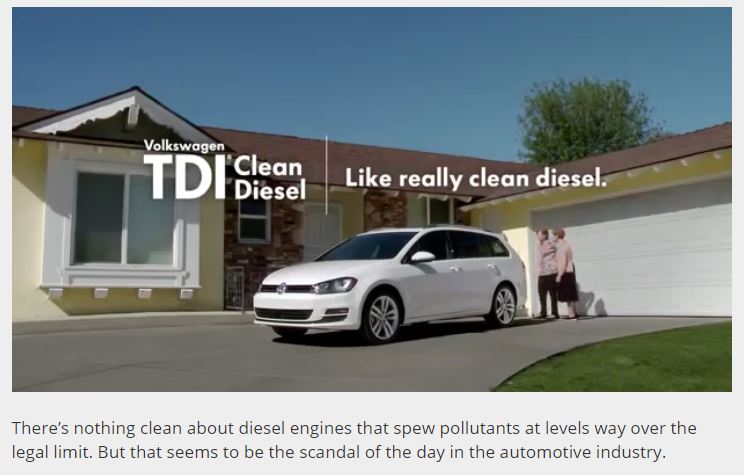

At the heart of the language game of bullshitting is the act of advancing empty and misleading claims. Recent linguistic analysis has identified the components of a statement that is bullshit. These are assertions which

(1) shows a loose concern for the truth,

(2) are driven by misrepresentation of intent and

(3) express undue certainty

Will you engage and reinforce or negate and undermine bullshit? The language game of bullshitting also entails how and if people respond to empty assertion. The shallow processing of empty and misleading claims happens when an individual who hears a bullshit claim doesn’t engage in meaningful inquiry through questioning or exploring a claim in more depth, letting it pass without any serious challenge. A second potential response is enthusiasm. This entails a more active and affirmative response whereby an actor faced with bullshit responds by joining in.

A final response to bullshitting is negation. This is when someone ‘calls bullshit’ by pointing out the false or misleading nature of a statement.

Identity – Yes, that’s You with a capital Y

An outdated habit and pattern of creating our identities is that we create roles around ourselves and never look out again. Participating in a language game is a form of identity work. It’s a way of creating, maintaining and in some cases undermining how others see us, and how we see ourselves.

Successful bullshitting enhances the image of bullshitters. This happens when bullshitters are able to more or less convincingly present themselves as more grandiose than they actually are. As a result, external audiences are more likely to make positive judgements about them and are more willing to invest resources in them.

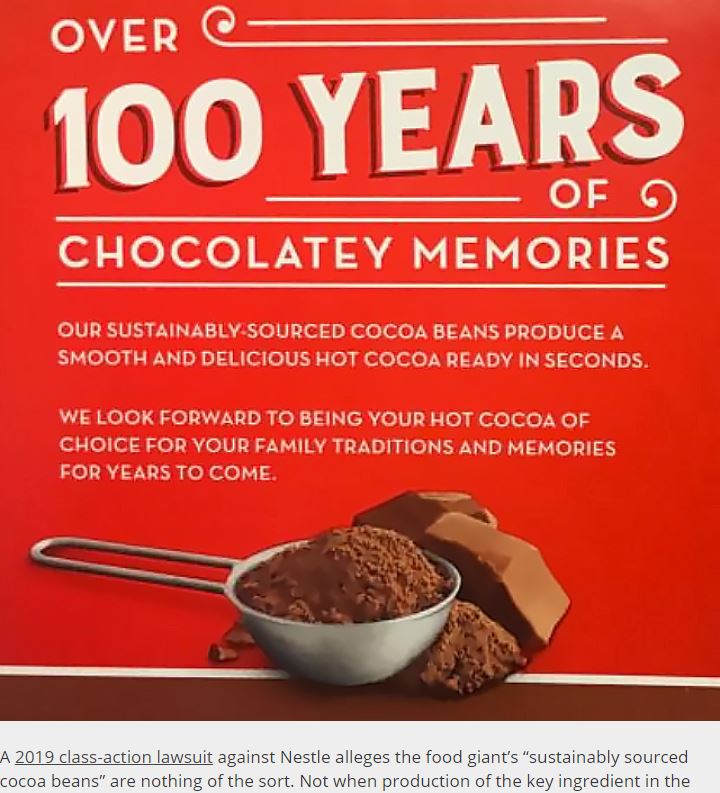

When bullshitting enhances an individual’s’ image and identity and no one challenges or questions them, they’re likely to engage in more of it. For instance, research shows that an organisation increases the scale of bullshitting when they use more empty and misleading phrases in their advertising to consumers.

A second way bullshitting might increase is through extending the scope. This is a qualitative shift where people bullshit about a wider range of issues or in a wider range of forums. For instance, an organisation would increase the scope of bullshitting if it had previously been bullshitting in their advertising to consumers but then also began bullshitting in communication with employees. An implication of increased scale and scope is that becoming a legitimate participant in the collective conversation also means bullshitting.

Additionally, veracious people get drawn into using bullshit just so they might be seen as having a legitimate voice in their organisation. Positive short term results from bullshitting can lead an organisation investing more into the speech community which encourages bullshitting. This means they are more likely to rely upon the management ideas industry as a source of input when making decisions, more likely to reward noisy ignorance and more likely to stoke up permission. Bullshitting becomes a language game which may appear to be useful in the short term but is harmful in the long term. It is allowed but not officially sanctioned.

Bullshitting is a common social practice in many organisations. In the previous section, I have argued that people engage in bullshitting to participate in a speech community, to get through day-to-day interactions within that community, and to reinforce a positive image and identity of themselves. Successful bullshitting begets more bullshitting. When this happens, what starts out as informal bullshitting can gradually become a collective routine, then part of the formal organisation and end up as sacred truth.

How do we recognise Bullshit?

The first rule of bullshit recognition is to expect it;

We must avoid becoming so accustomed to bullshit as to be indifferent to its presence;

Notice how colleagues go about framing statements, in written, spoken, or graphical form, that are without regard for the truth;

When faced with ‘jargonese,’ people often assume they’re missing something, or they confuse vagueness for profundity. The rule holds however, that if it is not possible to understand what the words in a statement mean, then it is reasonable to suspect the statement to be bullshit. (see some examples below)

Considerations

When leaders de escalate and de sacralise bullshit in a public and observable way, bullshit can be deformilised. ‘Calling out’ bullshit in an effective way is contagious and can lead to an entire organisation committing itself to avoiding management jargon, unnecessary acronyms and other forms of business bullshit. For instance, some organisations have adopted ‘no bullshit’ rules.

Train for Courageous Conversations , either as a group or one to one, to learn what and how to question the deep emotional and moral values attributed to a particular term. A powerful question has the capacity to “travel well”—to spread beyond the place where it began into larger networks of conversation throughout an organisation or a community. Questions that travel well are often the key to large-scale change.

Training for Courageous Conversations empowers voice, allowing people to SpeakUp to counter the harm of bullshit. Asking to see evidence that supports suspected bullshit and providing alternative statements, while being cognisant that simple and coherent bullshit will tend to be more appealing than intricate and complex truths, is challenging.

Onboarding and Career Transitions: Utilise these opportunities to explore an individuals’ existing values to begin to see if what they once thought of as sacred is indeed ‘bullshit’.

Encourage critical thinking, an approach to thinking that is reflective, sceptical, rational, open-minded, and guided by evidence. Critical thinking is the opposite of the quick, automatic, skim-based thinking that produces and spreads bullshit. Those who have the ability to stop and think analytically about the substance of statements are less receptive to bullshit.

Encourage people to question statistics and visualisations of data. They should know the consequences of confusing means and medians, correlation and causation, and the measurement errors that can accompany biased sampling, the inclusion of outliers, and the misspecification of variables and relationships in regression models.

Eliminate pointless meetings and committees – there is an increasingly prevalent view that meetings and committees do not provide sufficient value when they involve too many or the wrong people, have no agenda, and are run inefficiently. Organisations should only establish committees and have meetings when there are clear terms of reference, a value-adding agenda, and the right attendees who can contribute to the desired agenda. More simply, the need for a meeting should be questioned unless an important decision needs to be made.

Courageous Conversation training includes learning how to create an intentionally induced cognitive intervention that directs attention onto the ‘real’ features of a situation compared to anticipated or fear-exaggerated features by focusing on the description (but not the interpretation) of the situation.

I hope you enjoyed reading my blog. If you did, please pass it on, and get in touch, I’d love to help.