True Story: One of the LeisureNet joint CEOs, Peter, summonsed the project accountant, “Tony”, a senior manager, into his office. In rapid and hushed tones, Peter briefed Tony in the corridor saying that he had the directors of our largest offshore investors, Capvest, on the phone. The Capvest directors were irate having identified significant differences between Tony’s international financial budget and my more realistic international cashflow forecast.

‘Tony’ and I knew the reason for the disparities – Peter had instructed ‘Tony’ to perform ‘cosmetic surgery’ on the financial budget, to inflate the revenue, to discount our ratio of bad debts. ‘Tony’ obeyed. At the same time, I had been instructed to ensure that my cashflows, known as ‘Wendy Sheets’ were never to be provided to Capvest.

In light of Capvest’s investment of £17,3 million I had considered this dishonest and unfair and had left a Wendy sheet accessible on my desk when the Capvest directors had visited our South African offices from the UK.

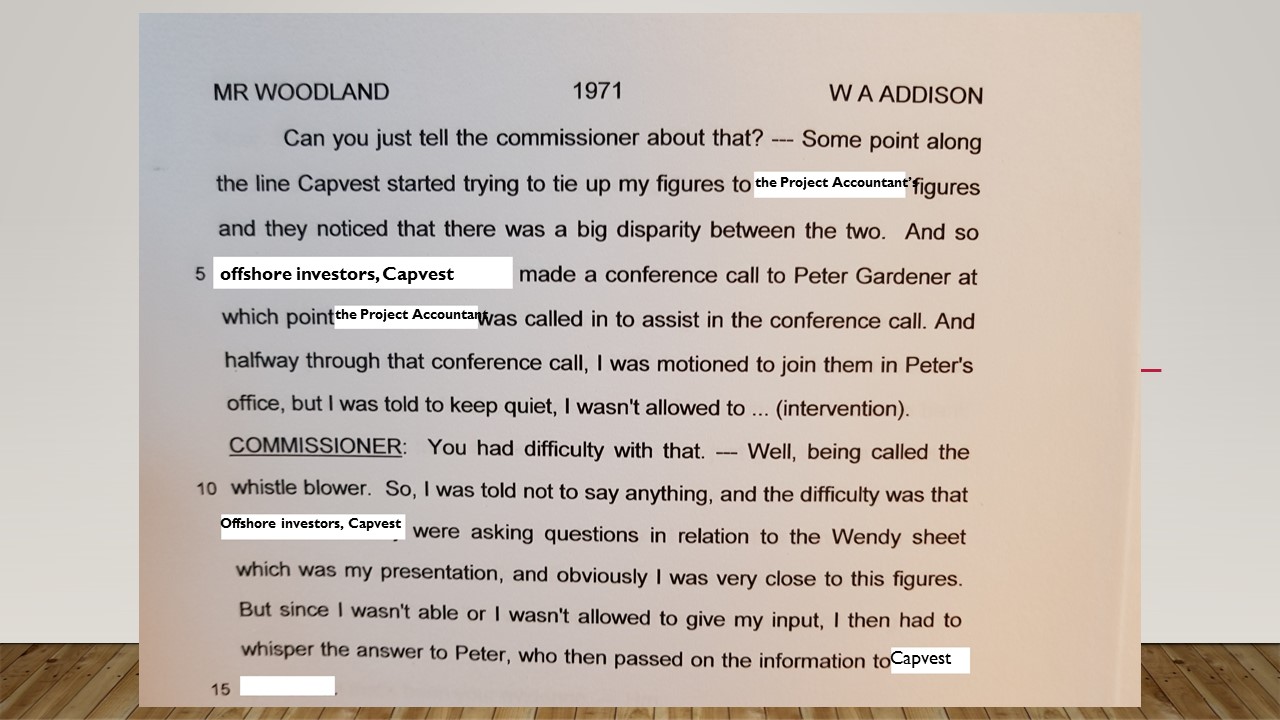

Below is a copy of a page from my Witness bundle where the prosecuting advocate is questioning me about the disparities, the secrecy and the Wendy Sheets.

‘Tony’ never spoke up, he didn’t push back against the unrealistic budgets. Instead, these cosmetically enhanced revenue streams became unrealistic sales targets, disseminated to Middle Managers, the International Sales Managers. They, in turn also never spoke up, nor did they question or challenge the figures. Instead, they expended an enormous amount of energy creating deceptive routines and the appearance of success, energy that could have been directed more honestly and productively.

The Middle Managers identified structural vulnerabilities in the organisation to exploit, create and enforce lower level routines from their sales team members in order to enable and sustain their deceptive performances. This was done through concerted efforts to coerce individuals to comply with the campaign of deceit.

Successful performances were feigned by middle management to make it seem as if everyone within their team was reaching their targets. And because senior management distributed rewards based on this performance, the deceit harmed the organisation’s bottom line. More significantly, the deceit also harmed the organisation because upper management made strategic decisions and allocated resources based on the sales team’s feigned success.

Goals, along with accountability measures, are often implicated in large scandals. The measures create new incentives and power dynamics which motivate workers to focus blindly on delivering the numbers that are expected even if through unethical means.

Organisational routines are complex and do not operate in a vacuum. They are enabled and constrained by their broader context and focus is more on operational action than on reflective cognition of the action. They consist of multiple patterns of action as well as multiple sub-routines that may be enacted by different sets of people throughout the organisation. While individuals might not have a detailed understanding of what all those others do exactly, individuals do tend to share a basic understanding of the overall routine as well as others’ sub-routines and roles This is important because, as research indicates, senior management and middle management as well as frontline workers all play a role in the social production of deceptive performances. Patterns of action, resulting in routines, are interdependent across levels, explaining how the processes behind collective forms of deceptive performance may involve action across all hierarchical levels.

Something else the majority of people share is the difficulty in speaking up the chain of command. This in itself becomes a pattern of non -action creating a social reality, an organisational climate, of silence.

As demonstrated in my situation, shared at the beginning of this blog, where, in the LeisureNet case, ‘Tony’, the Senior Manager remained mute and I was actively muted by the CEO, deceit cascaded down to the international sales managers. They in turn, instructed their sales teams on how to make sure senior management wouldn’t see anything they weren’t supposed to see. This pattern of deceit resulted in significant anxiety when senior management visited and teams would often, under the guidance of their manager, spend substantial amounts of time rehearsing for the visits.

Unethical, deceptive outcomes are likely transferable to any context that meets the following conditions to translate routines and sub-routines into corruptive patterns of action:

- Senior management imposing unrealistic expectations,

- the existence of performance constraints that make it difficult for middle managers to ethically translate expectations into practice,

- the existence of exploitable organisational structural vulnerabilities that allow deception.

- the absence of strong ethical norms to guide behaviour.

The most fundamental mitigation for deceptive outcomes is to build a culture of psychological safety so that all managers can argue for a revision of unrealistic goals. This, in addition to empowering individuals to challenge top management through the process of Courageous Conversations will create Climates of Voice.

Considerations

Consider the importance of understanding goal setting’s effects within a hierarchical context with multiple layers;

Think about goal setting in light of the hierarchy and the potential for routines and sub-routines to be corrupted;

Middle managers may use routines as tools to induce their subordinates to engage in widespread unethical behaviour;

Consider orchestrating ‘Speed Dating’ Exchanges between middle managers to ensure leaders address issues outside their units that impact their strategies.

If you’ve enjoyed reading my blog, please share.

I’d love to be of service; please get in touch.